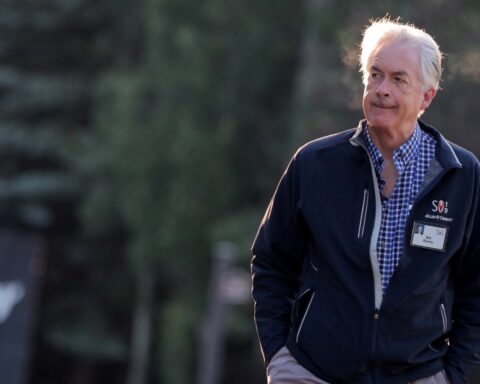

WASHINGTON – “It is very important to note that in almost every profession, perhaps beginning with brain surgery, amateurism was not seen necessarily as a remarkable and important attribute for success, but long studies, professionalism and deep involvement,” said Thomas R. Pickering, who spoke in support of experience at a forum on the future of U.S. diplomacy organized by the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington.

Pickering retired as a high-ranking career diplomat in the U.S. Foreign Service and is described as an “ambassador for all seasons” by some because of the number of major postings he held during a distinguished career.

There has long been tension between career diplomats, known collectively in the United States as foreign service officers, and individuals who are appointed to ambassadorships by incoming presidents because of their contributions, whether financial or otherwise, to the party in power.

Jendayi E. Frazer, a former assistant secretary of state for African affairs, argued that political appointees can bring added value to the State Department, even while acknowledging the challenges the appointed ambassadors invariably confront in leading career diplomats.

“Any political ambassador that goes into the State Department knows that they’re going into hostile territory,” she said. These political ambassadors often feel like “they have a target on their back” because of the perception that they bought their positions.

“That has to stop,” she said. “In fact, I think those career foreign service officers would do well to embrace those political appointees.”

Frazer said the political ambassadors can be “the very same people who can be your advocates” with the U.S. Congress in ways that career foreign service officers have not always been able to be. A political appointee, she added, can tell a foreign official, “I know the president; if necessary, I can pick up the phone,” even if that is not always true.

Robert D. Kaplan, a journalist turned foreign policy expert, emphasized the importance of paying attention to voices from the rank and file among career diplomats and others with on-the-ground knowledge.

“Most of Washington, most books, most discussions, focus on … the top layers of diplomacy. But it’s often the ‘down and in’ parts — the assistant secretaries downward to the deputy assistant secretaries, right down to the contractors” who are most knowledgeable about the countries in which they’re posted.

“The best briefings I’ve ever gotten as a journalist were from first and second secretaries at embassies,” he said. “It is these vital, lower-level people who need to be supported and given the opportunity to let their voices be heard as the top echelon makes foreign policy decisions.”

He said those rank-and-file diplomats should also be given the chance to “be able to come back [to Washington] and break conventional wisdom, come back with reports that go against the grain of the policy.”

In a recent book, The Good American, Kaplan described Bob Gersony, a former State Department contractor, as “the U.S. government’s greatest humanitarian.”