When Russia held large-scale military exercises in Belarus in February, the two countries described them as defensive in nature, aimed at repelling outside aggression, namely from Ukraine and NATO.

But as the exercises wound down, many of the 30,000 Russian troops stationed in Belarus then poured over the border of Ukraine as part of President Vladimir Putin’s invasion, now in its eighth month.

New satellite imagery obtained by RFE/RL’s Belarus Service shows thousands of Russian troops may have returned to Belarus, raising questions about whether another incursion into Ukraine from the north is imminent — or if Moscow, with the help of Minsk, is merely trying to distract Kyiv.

The Russians “don’t have enough combat power to launch an offensive [from Belarus], and there are no vital Ukrainian points nearby,” said Mark Cancian, a military analyst at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Russian forces have suffered significant losses in manpower and equipment since September, when Ukraine launched a counteroffensive that continues in the Donbas in the east and Kherson in the south.

“The Russians probably want to distract Ukrainians and pull some of their forces away from Kherson and the Donbas,” Cancian told RFE/RL.

Tent Encampments

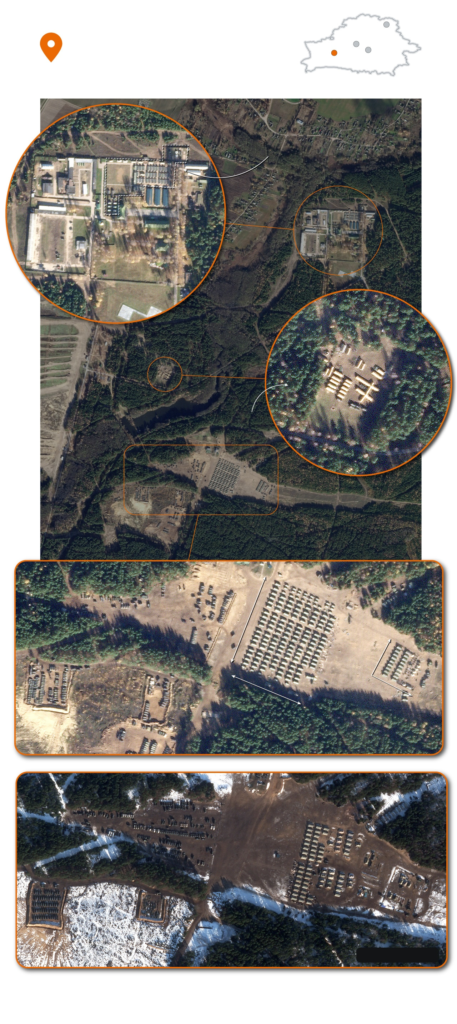

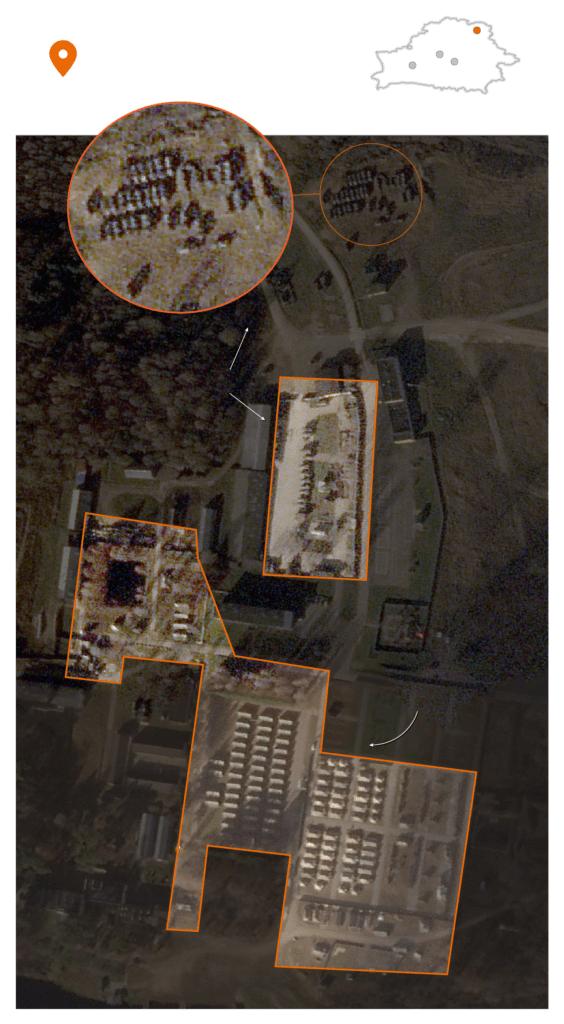

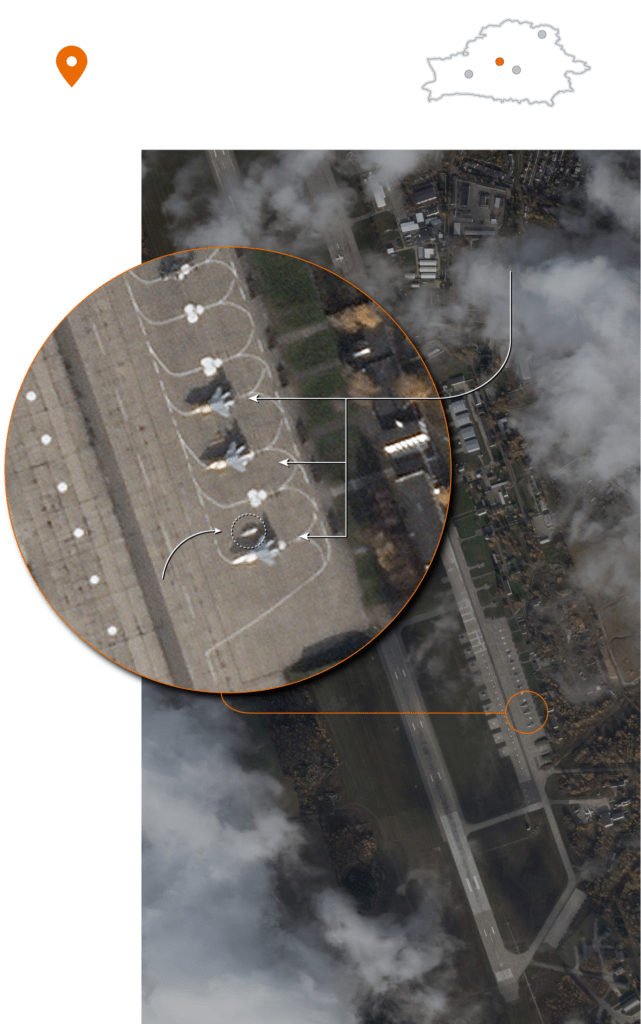

Satellite imagery captured by the commercial company Planet Lab on October 31 and obtained by RFE/RL shows Russia has set up more than 300 tents in three locations over the past month to temporarily house soldiers at three training grounds in Belarus.

They included at least 190 tents at Abuz-Lyasnouski in western Belarus where ground forces train, 35 in Repishcha in central Belarus where artillery forces exercise, and 80 in Lasvida outside Minsk where airborne forces train.

Abuz-Lyasnouski is the southernmost of the locations, located about 160 kilometers north of the Ukrainian border.

Hundreds of pieces of military hardware, including trucks and some howitzers, have arrived at the bases as well, according to the images.

Most of the tents appear to be 12 meters by 7 meters in size, which Dara Massicot, a military analyst at the Washington-based RAND Corp., estimated could comfortably hold up to 25 soldiers each.

That would imply a maximum of 7,500 troops could be stationed at those three locations.

It is unclear if more will tents be erected and how many Russian soldiers are being housed in pre-existing buildings and structures near the training grounds.

There’s been no public explanation from Russia as to the purpose of the camps nor the number of troops it plans to station in Belarus.

In Belarus, meanwhile, strongman Alyaksandr Lukashenka announced on October 10 that Russian troops would be deploying to Belarus, but he maintained it was for defensive purposes, asserting– without evidence — that Ukraine was planning an attack.

Days later, Lukashenka’s defense minister said a total of 9,000 troops would be deployed along with Belarusian forces near the Ukrainian border.

Ukrainian intelligence has claimed Russia plans to send up to 20,000 troops to Belarus, a force large enough to attempt an invasion.

Ukraine said they would be housed not just at bases but also civilian locations including warehouses, hangars, and abandoned agricultural farms. That would make it hard to determine the number of Russian troops in Belarus based on satellite imagery alone.

The deployment of Russian troops to Belarus may be an attempt by Minsk and Moscow to draw Ukrainian forces away from their counteroffensive in the east and south, according to the Institute for the Study of War.

They are trying “to pin Ukrainian troops against the northern border,” the Washington research organization said in a November 2 note.

The institute said it was “highly unlikely” Belarusian forces would take part in the war, noting it would strain the nation’s limited military resources and undermine Lukashenka’s hold on power in Belarus, which he has ruled for nearly 30 years.

Training, Not Deployment?

Analysts said there was another explanation for the appearance of the encampments in Belarus: Russia may be seeking to use them for training purposes because it doesn’t have enough capacity inside Russia.

“It’s plausible to believe that Russia needs the training areas,” Cancian said. “Mobilizing 300,000 reservists doubles the size of the army, [and] it’s not equipped to handle an expansion of that size.”

The Belarusian announcement of joint troop deployment came less than a month after the Kremlin ordered a major mobilization of military reserves aimed at bolstering Russian troop levels in Ukraine. Putin said on November 4 that Russia had called up 318,000 troops in all.

Mykhaylo Zhirokhov, a Ukrainian military expert, said Russia had sold off much of its land used as training grounds following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Even as its armed forces underwent a major modernization over the past 15 years, Russia had not invested in updating its recruitment and mobilization infrastructure, analysts said.

The lack of investment has showed up in the often chaotic and haphazard nature of the mobilization since September 21 — something that has been closely documented by Russian media.

Zhirokhov said it was possible Russia could order its troops into Belarus to invade Ukraine once their training finishes in the spring.

If so, some experts said, their fate could be far worse than the first wave of Russian soldiers who invaded from Belarus, who suffered heavy losses before retreating at the end of March.

That’s because Ukrainian forces are now better trained and more experienced, having fought months of grueling battles across the country. Ukrainian forces also now have powerful Western weaponry in their arsenals.