From Stranger Things re-enactments to Batman dining nights, interactive events are taking over town centres – and fans are willing to pay high prices for the Instagrammable privilege of participating

There is an industrial hydraulic machine in the Docklands of London that breathes in and out and has eyelids that flutter even when no one is watching. It took 18 months and more than a $1m to build, and according to Michael Orsino – senior vice-president of events group Cityneon – it is absolutely not a robot.

“We refer to them as creatures, even internally when we have our meetings,” Orsino says. “They truly do come alive so we try to stay away from calling them robots.” This blinking, breathing robot is a dinosaur – it stomps and roars in the finale of Jurassic World: The Exhibition, an immersive experience based on the film franchise. A “keepalive” system means the show’s dinosaurs move subtly even when no one’s about, “because we always want them to feel like they’re present”.

There are currently four Jurassic World exhibitions across the globe – London’s is the latest, a 20,000 square-foot human-made jungle in the ExCeL centre that opened in August. Eight miles away, in Soho, there is a dinner that requires a narrator and an interval. At the Monarch Theatre in the Batman-themed restaurant Park Row, diners eat 10 courses based on DC Comics characters – the experience features smoke machines, levitating dishes and the occasional magic trick.

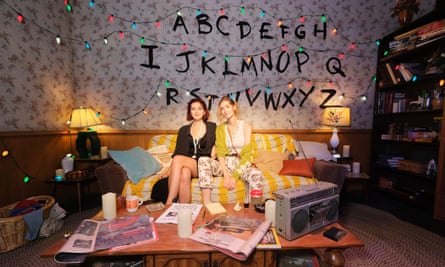

Welcome to the age of immersion. Dinosaurs and DC barely scratch the surface – this summer also saw the launch of Stranger Things and Tomb Raider “experiences” in London, an I’m A Celebrity Jungle Challenge in Manchester, and an Alice in Wonderland “immersive cocktail experience” in Sheffield.

By September, fans were able to re-enact Netflix’s Squid Game at Immersive Gamebox venues in London, Essex and Manchester. In the coming weeks, London will also host an experience based on the horror franchise Saw, while Cheshire will see thousands visit Harry Potter: A Forbidden Forest Experience. And that’s without mentioning the boom in immersive art experiences, the most recent of which – Frameless – has just opened in central London.

“The buzzword everyone will tell you is immersive-interactive,” Orsino says. “You hear that all the time.” As a small number of franchises dominate the cultural landscape, it seems each gets its own mini-Disneyland. But why are we suddenly obsessed with stepping into the screen? In an increasingly dark world, are we seeking escapism? Is this a balm for the infantilised, paralysed by property prices into a state of permanent adolescence? Or do we just want loads of cool pictures for Instagram?

Advertisement

“It’s really driven by a desire to find new ways to connect with our members and fans around the world,” says Greg Lombardo, head of live experiences at Netflix. The streaming service lost almost a million subscribers between April and July this year after subscription fees increased by £1 a month. The company is seemingly diversifying its income – tickets to Stranger Things: The Experience cost £52 per person, £62 on a Saturday.

“We really wanted to offer people a chance to feel like they were the hero of that story, that they had the powers,” Lombardo says. Guests are divided into different coloured teams and allocated a hand gesture they can use to remotely crush cans, unlock doors and battle monsters as they wander Stranger Things-inspired sets. The experience features exclusive footage from the show’s actors (Millie Bobby Brown is apparently contractually obliged to say, “Blue group, you are strong”) as well as live actors who interact with the audience.

“You can’t plan for it, you’re not hiding behind a script,” says Andrea Johannes, a 30-year-old actor in the experience. “It kind of keeps you on your toes.” Some audience members are superfans keen to interact, while others try to catch Johannes out – as Stranger Things is set in the 1980s, she has to feign ignorance of mobile phones. Johannes says immersive events have been a “blessing” for actors post-pandemic. “Here we are, all together, and it’s time to play around and be creative.”

For many, being accosted by a thespian pretending to be a scientist, wizard or dinosaur handler is a living nightmare, so why are more and more people seemingly seeking this out? Lombardo says the Stranger Things experience attracts all ages, while guests of The Queen’s Ball – a party based on Netflix’s hit show Bridgerton – are 87% women aged 18-45. Lombardo calls it “prom for adults” – attenders join fan-created Facebook groups to discuss how to prepare for the event.

“Prior to the pandemic we were seeing a real appetite for in-real-life experiences. I think it was only heightened during lockdown,” Lombardo says. “I think people are craving moments of community.”

Elizabeth Cohen is a communications professor at West Virginia University who studies audience responses to different types of media. She says fans have always wanted to enter fictional worlds but the internet allowed them to get their voices heard. “I think the internet made ‘geeking out’ more mainstream,” she says. “And what is mainstream is also more profitable.”

Cohen says immersion is psychologically gratifying because people connect with others, relieve stress and get creative. Just as we can both watch and play sports, Cohen says we can now watch and play with shows. Does this mean we’re big babies? “Sports fans often go to great lengths to dress up in support of their team, put on face paint, collect memorabilia,” Cohen says. “But I’ve never heard anyone suggest that sports fandom was infantilising, so why is there a double standard for pop culture?”

James Bulmer, creator of Batman restaurant Park Row and CEO of immersive group Wonderland says: “I’ve created this whole business to hold on to my childhood.” Bulmer, previously CEO of Fat Duck Group and a licensing head for Disney, had the idea for his company when walking past a film premiere in Leicester Square. “I got this feeling that these wonderful fans had nowhere to immerse themselves into the world that they all believe genuinely exists,” he says.

Bulmer “wanted to create venues that allowed you to put your day-to-day stresses behind you and dip into the most powerful emotion you have: nostalgia.” He says a “large percentage” of customers are millennials, and they’re willing “to pay a little bit more to get a much deeper value experience”.

Park Row’s tasting menu costs £195 a person, prepaid. Guests enjoy dishes such as hibiscus-coated ox tongue while screens play homage to comic books. Much of this, naturally, is designed to be snapped and shared. When enjoying “liquid nitrogen meringue popcorn” that makes your breath smoke, diners are told it looks “very cool on video”.

I’m not being cynical by saying everybody’s only worried by what they come back with on their phones

Attend any immersive experience and you have to be prepared to show up in a stranger’s camera roll. “We’ve seen it first-hand, this desire to take pictures of everything,” Bulmer says, referencing a TikTok of the restaurant that got 10.7m views.

“I’m not being cynical by saying everybody’s only worried by what they come back with on their phones,” says David Hutchinson, CEO of The Path Entertainment Group, the company behind Saw: The Experience. “Social media is a humongous part of our lives.”

Will Dean, CEO of Immersive Gamebox, says punters come away with a “curated gif” of their experience. For £34, you don a visor fitted with motion sensors and undergo the challenges featured in Squid Game inside a box room with screens for walls. Dean says he’s opening 80 new units in the US and UK next year; many are inside shopping malls. “We all know that department stores don’t drive foot traffic any more,” Dean says; restaurateur Bulmer says he planned to “completely disrupt the high street”.

In 2021, almost 50 shops a day closed down in the UK, while one in five nightclubs have shut in the last three years. Last year, The Path Entertainment Group opened an immersive Monopoly experience in an old Paperchase store on Tottenham Court Road; they plan to open Saw in an old nightclub. “After Covid there is a lot of space available on the high streets that we previously wouldn’t have been able to get near,” Hutchinson says.

Millions have been invested into immersion, but some experiences are rougher round the edges than others. Many last an hour – meaning prices feel extortionate when you consider a day ticket to Disneyland Paris can cost just £50. It remains to be seen whether they will attract repeat customers, or if they’ll quickly become associated with the forced fun of work socials and first dates.

The precedent for all of this is the 15-year-old immersive movie-going experience Secret Cinema; in 2019, the company took £8m for a screening of Casino Royale. Yet the pandemic disrupted the company’s profits, with turnover falling more than 60% between 2019 and 2020. Last month, ticketing firm TodayTix purchased Secret Cinema for $100m (£88m) and announced an intention to expand globally, looking for permanent locations in London, LA and New York. All this despite the fact that Secret Cinema has never made an annual profit.

Lockdowns may no longer be closing down live events, but we are now in the midst of a cost of living crisis and the appetite for immersion may drop off.

Or perhaps spiralling inflation will only increase the desire to step into the screen. “If you think about shows like Stranger Things or Bridgerton, they are escapist stories,” Lombardo says. “They allow us to forget, for a moment, things that might be more challenging in our lives.”

… we have a small favour to ask. Millions are turning to the Guardian for open, independent, quality news every day, and readers in 180 countries around the world now support us financially.

We believe everyone deserves access to information that’s grounded in science and truth, and analysis rooted in authority and integrity. That’s why we made a different choice: to keep our reporting open for all readers, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay. This means more people can be better informed, united, and inspired to take meaningful action.

In these perilous times, a truth-seeking global news organisation like the Guardian is essential. We have no shareholders or billionaire owner, meaning our journalism is free from commercial and political influence – this makes us different. When it’s never been more important, our independence allows us to fearlessly investigate, challenge and expose those in power.