During 2022 we celebrate the 13th Anniversary of National Fossil Day! Join paleontologists, educators, and students in fossil-related events and activities across the country in parks, classrooms, and online during National Fossil Day. National Fossil Day is an annual celebration held to highlight the scientific and educational value of paleontology and the importance of preserving fossils for future generations.

Age of Dinosaurs

Introduction

Dinosaurs are among the most popular and iconic fossil organisms, and dinosaur bones and tracks are favorite attractions at several National Park Service units. Body and trace fossils of non-avian dinosaurs have been documented from at least 21 NPS areas. Geographically, this record spans across the continental United States, from Big Bend National Park (Texas) to Springfield Armory National Historic Site (Massachusetts), and north to Denali National Park and Preserve (Alaska), but is centered on the Colorado Plateau.

Getting to know Dinosaurs

Dinosaurs through Geologic Time

All dinosaurs (aside from birds) lived and died in the Mesozoic Era. The Mesozoic (252 to 66 million years ago) was the “Age of Reptiles.” Dinosaurs, crocodiles, and pterosaurs ruled the land and air. As climate changed, sea levels rose world-wide and seas expanded across the center of North America. Large marine reptiles such as plesiosaurs, along with the coiled-shell ammonites, flourished in these seas. Common Mesozoic fossils include dinosaur bones and teeth, and diverse plant fossils.

The Mesozoic Era is further divided into three Periods: the Triassic, the Jurassic, and the Cretaceous.

Park fossils document dinosaurs from the Late Triassic (approximately 210 million years ago) to the end of the Cretaceous (66 million years ago). This encompasses everything from some of the earliest known dinosaurs of North America, to desert trackmakers of Early and Middle Jurassic age, to giant sauropods and plate-backed stegosaurs of the Late Jurassic, to new discoveries from the Early Cretaceous through the early Late Cretaceous , to tyrannosaurs and titanosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous.

- Triassic Dinosaurs251.9 to 201.3 Million Years Ago

- Jurassic Dinosaurs201.3 to 145.0 Million Years Ago

- Cretaceous Dinosaurs145.0 to 66.0 Million Years Ago

Triassic Dinosaurs

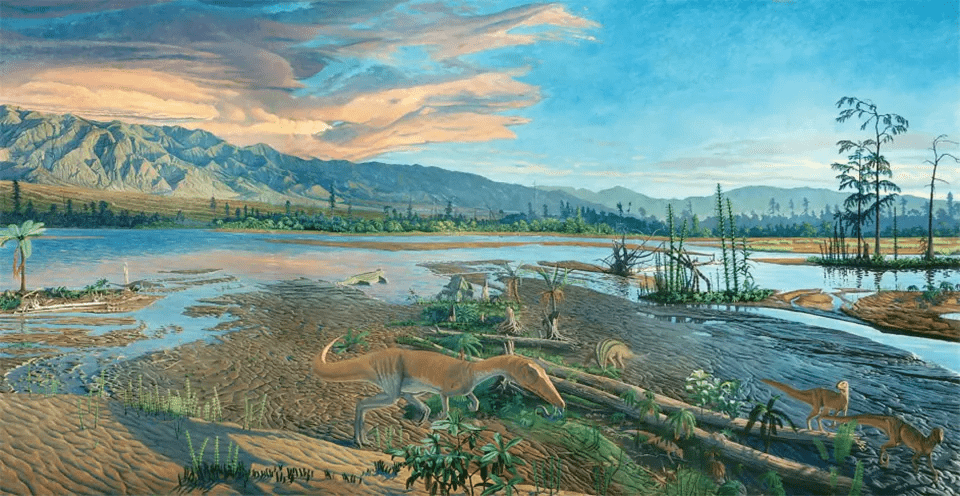

Triassic life and landscape visitor center mural. Dinosaur State Park, Connecticut. Dinosaur State Park is a designated National Natural Landmark.

Friends of Dinosaur Park and Arboretum mural by William Sillin.

Introduction

Dinosaurs evolved in a world that had one supercontinent, Pangaea, surrounded by one ocean, Panthalassa. The Atlantic Ocean did not exist; instead, Africa was joined to North America along much of what would be today’s Atlantic coast, forming the arid and inhospitable interior of the supercontinent. The Appalachian Mountains were much taller and more rugged. To the west, today’s Pacific coast did not exist yet, either. Instead, the land that would become the Pacific coast states was either not yet attached to North America or was under water. The Colorado Plateau and the Rocky Mountains did not exist yet, and in their place were vast lowlands near sea level. Volcanoes fringed the western margin of the continent.

The ancestors of dinosaurs were one of several groups of reptiles that benefited from the Permian–to–Triassic extinction approximately 252 million years ago. These ancestors were lightly built two-legged animals, around the size of a crow. Our best evidence of the earliest dinosaur ancestors comes from South America. True dinosaurs evolved by approximately 233 million years ago, early in the Late Triassic, and spread across the connected continents.

The record of dinosaurs in North America begins during the Late Triassic, approximately 225 million years ago. These early dinosaurs were mostly small, lightly built two-legged carnivores, including animals such as Coelophysis and its close relatives. Larger carnivorous and herbivorous dinosaurs are represented by tracks. Dinosaurs were not a major part of Late Triassic faunas, which include a wide variety of amphibians, mammal cousins, and reptiles, most famously the crocodile-like phytosaurs and the armored aetosaurs. Almost all of these other groups would go extinct at the end of the Triassic, 201 million years ago, in a major extinction event generally thought to have been caused by massive volcanic activity. Mammal cousins, the ancestors of today’s amphibians and reptiles, pterosaurs, marine reptiles, and dinosaurs persisted.

Triassic Dinosaurs in Parks

Dinosaurs from Triassic rocks (252 to 201 Ma) in the NPS are best known from Petrified Forest National Park (Arizona), which has most of the few Triassic dinosaur body fossils from the NPS. The park’s Triassic dinosaurs were “supporting players” in an ecosystem dominated by crocodile-like phytosaurs, armored aetosaurs, and giant amphibians. Other Triassic NPS dinosaurs are known almost entirely from tracks, mostly representing small three-toed predators. At Gettysburg National Military Park (Pennsylvania) and Valley Forge National Historical Park (Pennsylvania), visitors may see Triassic dinosaur tracks in locally quarried building stone.

Jurassic Dinosaurs

Introduction

The beginning of the Jurassic is marked by rifting between North America and other continents, leading to vast outpourings of lava and the beginning of the Atlantic Ocean. As North America drifted north during the Jurassic, parts of it tracked across arid latitudes that promoted the formation of enormous deserts. Sandstone rocks formed in these deserts contribute to the colorful landscapes of the Colorado Plateau. At other times, shallow seas flooded parts of the West. By the end of the Jurassic, both extremes were replaced by broad floodplains hosting a variety of organisms, including dinosaurs.

Dinosaurs diversified greatly after the extinction at the end of the Triassic removed most of their competition. We have bones and/or footprints of most of the major lineages of dinosaurs dating back to the Early Jurassic: carnivorous theropods; the enormous sauropods with their long necks and long tails; armored dinosaurs, including plated stegosaurs and scute-bearing ankylosaurs; and ornithopods, bipedal beaked herbivores. Dinosaur body fossils are rare in rocks of Early and Middle Jurassic age in North America, but tracks are locally abundant. Although there are some tracks and fossils from New England and the mid-Atlantic states, most North American dinosaur fossils from throughout the Mesozoic come from the western half of the continent. This is simply an accident of geology and geography: the western half of the continent is where rocks of the right age to have dinosaur fossils were deposited and are now exposed.

By the Late Jurassic, conditions were right to preserve large numbers of dinosaur fossils in a rock unit called the Morrison Formation. Many of the most famous dinosaurs of North America are from the Morrison Formation, such as Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, Brontosaurus, Diplodocus, and Stegosaurus. Pterosaurs and mammals diversified, and turtles and crocodiles were also abundant. Birds evolved from a group of small theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic, but these early birds have not yet been found in North America.

Jurassic Dinosaurs in Parks

The Jurassic (201 to 145 Ma) record of dinosaurs in the NPS is largely confined to the Colorado Plateau and Yellowstone area. Most finds can be put into one of two categories: tracks from rocks of Early (201 to 174 Ma) or Middle Jurassic age (174 to 163 Ma), or body fossils from the Morrison Formation, of Late Jurassic age (163 to 145 Ma). Jurassic dinosaur tracks have been found in many of the NPS units of the Colorado Plateau, and more are being found every year due to increased interest. These tracks are important because the host rocks have few body fossils, so the tracks are our only evidence of the dinosaurs. Tracks of small to large three-toed predators are most abundant. The Morrison Formation is known worldwide for its fossils of dinosaurs, from predators such as Allosaurus and Ceratosaurus, to enormous sauropods such as Apatosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Brontosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Diplodocus, to the bipedal herbivore Camptosaurus and plated Stegosaurus. The Dinosaur Quarry of Dinosaur National Monument (Colorado and Utah) is one of the most productive dinosaur sites in the Morrison Formation, and has yielded skeletons that are mounted in many museums. Several other parks also have Morrison Formation fossils, mostly in Colorado and Utah, but as far northwest as Yellowstone National Park.

Cretaceous Dinosaurs

Introduction

The Cretaceous Period of North America had several distinct phases. For approximately the first third to the first half of the period, conditions were generally similar to the Late Jurassic. Toward the middle of the Cretaceous, rising sea levels driven by the ongoing breakup of Pangaea submerged the shallow lowlands of the center of the continent, while the western margin was thrust up into a volcanic mountain range similar to the Andes as it overrode oceanic crust. North America was like two continents at this time—a narrow western landmass and a broader eastern landmass—with the Western Interior Seaway between them. Near the end of the Cretaceous, the seas retreated and the Rockies began to push up. North America was close to its current position and shape.

The dinosaurs of the Early Cretaceous, before the Seaway, are a mix of Jurassic-like holdovers and newer forms. The long, low Diplodocus-like sauropods and the plated stegosaurs went extinct, while ankylosaurs and ornithopods diversified. Sickle-clawed theropods became significant small carnivores. We don’t know much about the dinosaurs that lived in North America during the height of the Seaway, although there are many fossils of marine reptiles and pterosaurs in the marine rocks. Therefore, it is not clear how the Early Cretaceous dinosaurs transitioned to the dinosaurs known from near the end of the Cretaceous, which were much different.

The dinosaurs of the last 10 million years of the Cretaceous in North America are some of the best known in the world. They include tyrannosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus, diverse small theropods, ankylosaurs, bone-headed pachycephalosaurs, horned and frilled ceratopsians such as Triceratops, and “duckbilled” hadrosaurs. Sauropod dinosaurs seem to have gone extinct in North America around the time of the Seaway, to be reintroduced a few million years before the end of the Cretaceous. The new faunas may have something to do with the introduction and spread of flowering plants.

The end of the Cretaceous is famously marked by a major extinction that killed off all dinosaurs except birds, many groups of early birds, pterosaurs, marine reptiles, shelled squid-like ammonites, and many other groups. This extinction is attributed to an impact in the Yucatan.

Dinosaur Discoveries

The first report of dinosaurs associated with places that would one day be protected in the National Park Service goes back to the Lewis and Clark expedition. On July 25, 1806 near Pompey’s Pillar in Montana, William Clark found a large fossil bone that was likely from a dinosaur. This was along what is now commemorated in Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail. The study of dinosaurs in North America began in earnest in the 1850s, and one of the first specimens to include more than a bone or two was recovered from Springfield Armory in 1855. This specimen was described as a small herbivore, Megadactylus polyzelus (renamed Anchisaurus). Probably the most significant event for the study of dinosaurs in NPS areas was Earl Douglass’s discovery of what would become the Dinosaur Quarry on August 17, 1909, eventually leading to Dinosaur National Monument (Utah/Colorado) and the famous quarry wall display. To the south, expeditions to collect dinosaur fossils in the future Big Bend National Park (Texas) began in the 1930s.

Dinosaur-related scientific work has been increasing in the NPS since the late 1970s. For example, over that time span there have been significant footprint finds in Alaska and the Colorado Plateau. Also, 14 of the 19 dinosaur species named from fossils found in or associated with NPS areas have been named since 1988.

Non-Avian Dinosaurs Named from Fossils Collected in Parks

Show 102550100 entriesSearch:

| Species | Park | Citation | Age | Formation | Specimen | Notes |

|---|

| Agujaceratops mavericus | BIBE | Lehman et al. 2017 | Late Cretaceous | Aguja | TMM 43098-1 | Ceratopsian |

| Chasmosaurus mariscalensis | BIBE | Lehman 1989 | Late Cretaceous | Aguja | UTEP P.37.3.086 | Ceratopsian, now known as Agujaceratops mariscalensis |

| Angulomastacator daviesi | BIBE | Wagner and Lehman 2009 | Late Cretaceous | Aguja | TMM 43681-1 | Hadrosaurid |

| Aquilarhinus palimentus | BIBE | Prieto-Márquez et al. 2020 | Late Cretaceous | Aguja | TMM 42452-1 | Hadrosaurid |

| ?Gryposaurus alsatei | BIBE | Lehman et al. 2016 | Late Cretaceous | Javelina | TMM 46033-1 | Hadrosaurid |

| Texacephale langstoni | BIBE | Longrich et al. 2010 | Late Cretaceous | Aguja | LSUMNS 20010 | Pachycephalosaurid |

| Richardoestesia isosceles | BIBE | Sankey 2001 | Late Cretaceous | Aguja | LSUMGS 489:6238 | Theropod |

| Bravoceratops polyphemus | BIBE | Wick and Lehman 2013 | Late Cretaceous | Javelina | TMM 46015-1 | Ceratopsian |

| Camptosaurus aphanoecetes | DINO | Carpenter and Wilson 2008 | Late Jurassic | Morrison | CM 11337 | Ornithopod, sometimes known as Uteodon aphanoecetes |

| Dryosaurus elderae | DINO | Carpenter and Galton 2018 | Late Jurassic | Morrison | CM 3392 | Ornithopod |

| Uintasaurus douglassi | DINO | Holland 1919 | Late Jurassic | Morrison | CM 11069 | Sauropod, now considered a synonym of Camarasaurus lentus |

| Apatosaurus louisae | DINO | Holland 1915 | Late Jurassic | Morrison | CM 3018 | Sauropod |

| Camarasaurus annae | DINO | Ellinger 1950 | Late Jurassic | Morrison | CM 8942 | Sauropod, now considered a synonym of Camarasaurus lentus |

| Abydosaurus mcintoshi | DINO | Chure et al. 2010 | Early Cretaceous | Cedar Mountain | DINO 16488 | Sauropod |

| Allosaurus jimmadseni | DINO | Chure and Loewen 2020 | Late Jurassic | Morrison | DINO 11541 | Theropod |

| Koparion douglassi | DINO | Chure 1994 | Late Jurassic | Morrison | DINO 3353 | Theropod |

| Dystrophaeus viamalae | OLSP | Cope 1877 | Late Jurassic | Morrison | USNM 2364 | Sauropod, found within a quarter mile of Old Spanish Trail |

| Chindesaurus bryansmalli | PEFO | Long and Murry 1995 | Late Triassic | Chinle | PEFO 10395 | Theropod or other early dinosaur |

| Megadactylus polyzelus | SPAR | Hitchcock Jr. (in Hitchcock 1865) | Early Jurassic | Portland | ACM 41109 | Sauropod cousin, now known as Anchisaurus polyzelus; specimen found at Springfield Armory but not in the part included in the historic site; the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature has since transferred holotype status to another specimen (ICZN 2015) |

Museum Learning Center celebrates National Fossil Day and more

The Sainte Genevieve Museum Learning Center has a busy October ahead, with multiple activities planned throughout the month, including a whole week to celebrate National Fossil Day on Wednesday.

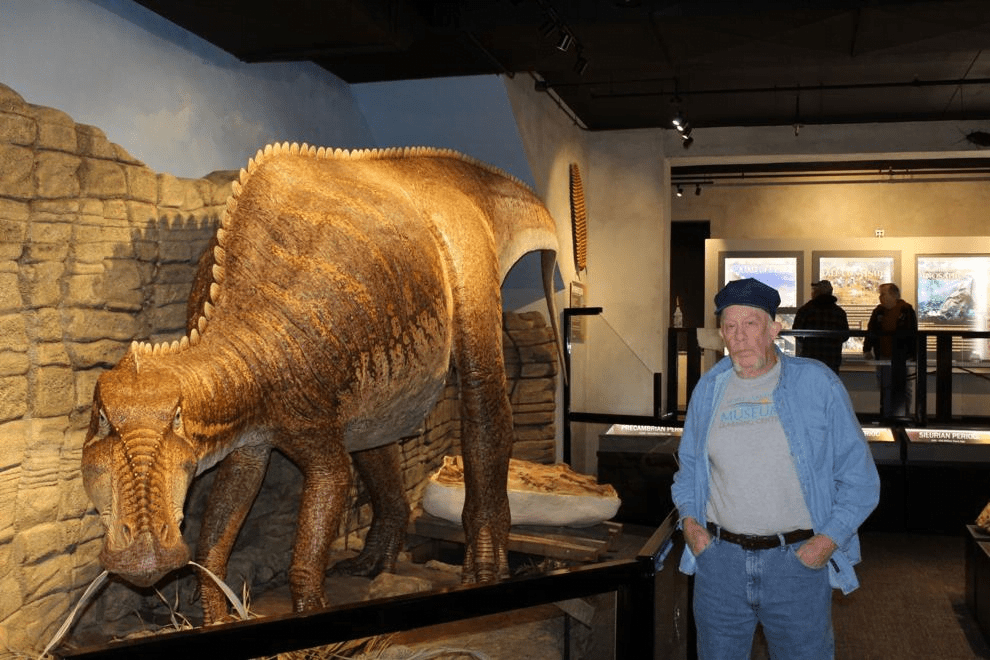

Every Friday during the month of October visitors can enjoy fun and interactive activities at the museum. At 10:30 a.m. visitors can discover dinosaurs with a hands-on learning experience in the Hall of Giants. The Hall of Giants allows guests to experience the thrill of being up-close and personal with life-sized dinosaurs and discover the stories fossils can reveal about the past. At 1:30 p.m., guests will enjoy a video presentation on the history of the Missouri dinosaur during the “Show-Me-Dino” time slot. Also on Fridays, multiple guided tours will be available through the day.

The Missouri dinosaur is the Parrosaurus missourienis, a duck-billed dinosaur discovered in Bollinger County, near Glen Allen.

While National Fossil Day is Wednesday, the museum has plans for nearly every day of this week.

On Wednesday, in celebration of National Fossil Day, the museum will have a guest speaker, who has not been announced yet. This year marks the 13th anniversary of National Fossil Day, as it was celebrated first in 2010 as a fossil-focused day during Earth Science Week. This year’s event starts at 10:30 a.m. on Wednesday.

Thursday is Discovery Playdate. From 10:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m., children ages 2-5 can enjoy a fun and interactive learning activity theme. This month’s theme for the play date revolves around fossils due to National Fossil Day. Children must be accompanied by an adult, and regular admission will apply. Children 5 and under are free.

Friday is the Discovering Dinosaurs exhibit, starting at 10:30 a.m. with the discovering dinosaurs, followed by a video presentation on the history of the Missouri dinosaur.

On Saturday and Oct. 28 from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m., University of Missouri-St. Louis Professor Emeritus Michael Fix will be working to uncover the Missouri dinosaur, which will be uncovered piece by piece, bone by bone, at the Sainte Genevieve Museum Learning Center.

The Museum Learning Center will also host a Vintage Tractor Display on Oct. 22 as part of the Rural Heritage Day in Ste. Genevieve.

On Oct. 26, the museum is allowing guests to bring in any fossils, rocks, teeth, bones, and more to get an expert’s opinion on what the item is, where the item came from, and when the item originated. This event starts at noon and end at 3 p.m.

Located at 360 Market Street in Ste. Genevieve, the museum can be contacted by phone at 573-883-3466, email at contact@stegenmuseum.org, online at stegenmuseum.org, or Facebook under Sainte Genevieve Museum Learning Center. The museum is open daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and features exhibits such as the Hall of Giants, ancient cultures gallery, and a gallery all about the history of Ste. Genevieve through the eyes of more than just the French.