WASHINGTON — A U.S. diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Olympics would deal a blow to Seoul’s attempts to resume diplomacy with North Korea, experts said.

Last week, U.S. President Joe Biden said that his administration was “considering” a diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Winter Olympics in February.

Such a boycott would mean the U.S. would not send government officials to the Winter Games although it would allow athletes to compete.

Many human rights groups and some lawmakers in Congress called for a U.S. diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Olympics, citing Beijing’s human rights abuses.

South Korea has been pushing for a declaration to end the Korean War. That war concluded with the Korean Armistice Agreement in 1953, which announced a cease-fire rather than complete peace.

Diplomatic setback

In his address to the U.N. General Assembly in September, South Korean President Moon Jae-in said such a declaration could be a “catalyst” for the resumption of dialogue with North Korea.

Seoul sees an end-of-war declaration as the key to jump-starting nuclear talks with North Korea, which have been stalled since October 2019. It also believes the Beijing Olympics will offer a diplomatic venue where the leaders of the U.S., China, South Korea and North Korea could discuss such a declaration.

“An end-of-war declaration in particular is … almost a last-ditch effort by President Moon. So I would not be surprised if they tried to engage in Olympics diplomacy again,” said Olivia Enos, senior policy analyst in the Asian Studies Center at The Heritage Foundation.

“But I think those efforts will be likely futile,” added Enos.

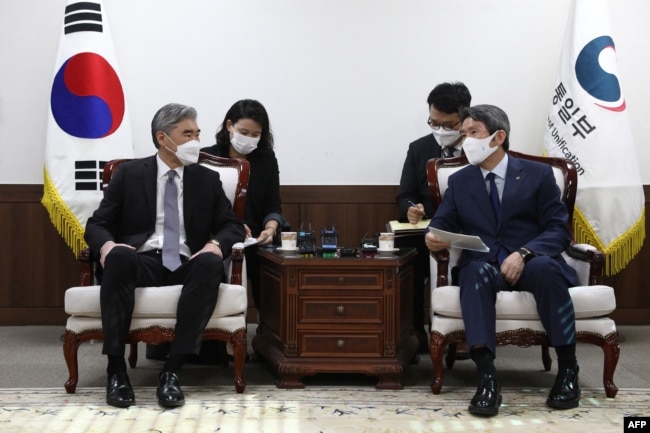

On Friday, South Korea Minister of Unification Lee In-young said that Seoul and Washington held “very serious, deep consultations regarding the end-of-war declaration,” and that “those discussions are entering a final stage.”

Washington, however, has not publicly endorsed Seoul’s proposal. After talks with her South Korean and Japanese counterparts last week, U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman said that the U.S. was “very satisfied with the consultations” with Seoul and Tokyo on the issue, without giving further details.

Security concerns

Washington has been reluctant to accept Seoul’s proposed end-of-war declaration out of concern it could undermine the security of East Asia, according to experts.

Bruce Klingner, senior research fellow for Northeast Asia at The Heritage Foundation, said, “The U.S. is not interested in an end-of-war declaration but is discussing it only since a valuable ally has raised the topic.”

David Maxwell, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, said, “The U.S. is also concerned with the political warfare strategy of North Korea, China and Russia. They have already laid the groundwork to blame the U.S. for not reaching an end-of-war declaration.”

VOA’s Korean Service sought comment on an end-of-war declaration from South Korea’s presidential office but did not get a response.

Potential consequences

Some raised concerns that declaring a formal end to the war could undermine the presence of the United Nations Command (UNC) in South Korea, which could lead to calls for the withdrawal of U.S. troops from the country.

Bruce Bennett, an adjunct international/defense researcher at the RAND Corporation, said, “The declaration could provide some sort of a justification for North Korea to push for the termination of the armistice agreement and dissolution of UNC.”

As a U.S.-led multilateral military force, the UNC defends South Korea and upholds the Korean Armistice Agreement.

“We would back our way into dissolving the only internationally recognized legal instrument that has prevented the resumption of hostilities on the peninsula” because there will be calls to rescind U.N. Security Council Resolution 84, which activated UNC, said General Robert Abrams, former commander of United States Forces Korea, during a virtual forum held by The Korea Society last week.

Earlier this month, North Korea’s U.N. ambassador, Kim Song, said, “Immediate measures should be taken to dismantle the UNC in South Korea.”

An end-of-war declaration, however, does not have the legal power to automatically end UNC or the armistice agreement but, nonetheless, could provide a justification for such calls, according to Klingner.

Klingner said that aside from its impact on UNC, precipitously declaring the war’s end could “generate a domino effect advocacy” for other actions that could undermine security in the region, such as removing about 28,000 U.S. troops from South Korea and ending joint U.S.-South Korea military exercises.

Scott Snyder, director of the program on U.S.-Korea policy at the Council on Foreign Relations, said, “The main effect of an end-of-war declaration is that it misrepresents the real situation on the ground.” Snyder added: “The key to achieving an end-of-war declaration is to achieve the conditions of peace necessary to declare that the war is indeed over.”