A trickle of water in southwestern Iran has turned into a torrent of protests against the clerical establishment in Tehran.

Just months after the authorities resorted to deadly force and empty promises to tamp down mass protests, locals in the region have joined farmers to demand government action to replenish water supplies drained by decades of mismanagement.

Videos show tens of thousands of people gathered in the ancient city of Isfahan, where the Iranian Plateau’s “giver of life” — the Zayandehrud River — now runs dry for much of the year.

“Give back the Zayandehrud! Give Isfahan life!” a crowd can be heard chanting in the city’s central square, one of the world’s largest, in a clip shared with RFE/RL’s Radio Farda:

In another demonstration, hundreds of ordinary citizens joined farmers who have been gathering in the shadow of the historic Khaju Bridge for weeks to protest the authorities’ decision not to release water into the Zayandehrud this fall.

In protests staged on the dry riverbed that have extended through the nights over the past week, participants have declared that the river’s waters are “the right of every Isfahan resident”:

Women have also shown up in large numbers to lend their voices:

Officials often attribute the dire situation to seasonal drought in the once-marshy area, but critics point to large-scale development projects like the Chadegan dam that has regulated the Zayandehrud since the early 1970s, and the depletion of nonreplenishable aquifers.

Protesters have been particularly focused on the diversion of water to other regions of the country. While the practice dates to the 16th century, rapid population growth and industrialization has demanded greater amounts of water, fueling discontent in other areas where local supplies are seen as a solution.

Following in the footsteps of protesters in Isfahan, citizens have also demonstrated 80 kilometers southwest in Shahrekord, the capital of Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari Province.

“This is Chaharmahal. Taking water is forbidden,” long lines of demonstrators declared this week in protest of purported plans to draw water from the Beheshtabad River.

“Today our water! Tomorrow our soil!” locals chanted on November 23:

Truckers have also loudly made their position known, with convoys of vehicles blaring their horns to protest the idea of taking more water from Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari Province:

Such scenes are not new. In neighboring Khuzestan Province, residents erupted with anger over electricity blackouts and water shortages in July, sparking demonstrations dubbed the “uprising of the thirsty.”

As the movement spread to other parts of the country and provided a vehicle for vocal criticism of the clerical regime in Tehran, security forces responded with violence.

At least 11 people in the oil-rich province were killed in the crackdown, which Amnesty International said included the authorities’ use of “deadly automatic weapons, shotguns with inherently indiscriminate ammunition, and tear gas.”

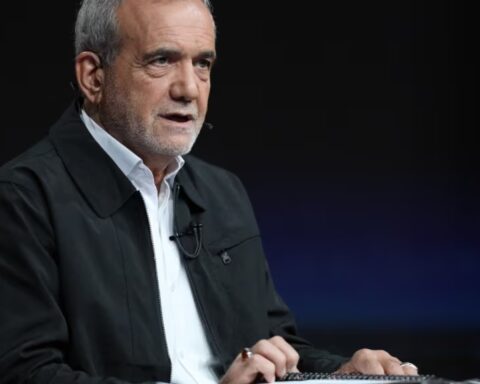

The protests lasted more than a week until Iran’s newly elected president, Ebrahim Raisi, vowed that solving Khuzestan’s issues would be one of his administration’s top priorities.

“We will support the province in dealing with water issues and other problems,” Raisi said during a phone conversation with the local governor on July 25.

This week, Raisi met with representatives from multiple provinces, including Isfahan, in an effort to resolve the crisis. But the source of the problem is not going away anytime soon and is not limited to the country’s southwest.

The latest report by the Iran Water Resources Management Company said that the supply of water in the country’s reservoirs was down 27 percent compared to 2020, leaving them at less than 40 percent capacity.

The situation has led to warnings that there is barely enough water in reserve to supply the country through the autumn. On November 23, the head of the Tehran Regional Water Supply Company, Mohammad Shahriari, was quoted by state media as warning that the situation in the capital “is more critical than expected, and if we do not find a cure now, we will face many problems.”

Some, like the farmers of Isfahan, never stopped their protests. Now, after weeks of inaction by the government, the ranks of demonstrators have been significantly boosted.

And unlike water supplies, there is no shortage of additional fuel for protests, including the return of annual deficits of natural gas, the remembrance of those martyred in previous demonstrations, and, in Isfahan, knowledge that the region is the most polluted in Iran.

For the government in Tehran, meanwhile, the issue is showing signs of spilling abroad and even into cyberspace.

Following a spate of cyberattacks on Iranian infrastructure, including the country’s dams, state media signaled that the situation has left the authorities cut off from access to data about water reserves.

And in Iraq, officials have accused Iran of siphoning off river water before it reaches its own strategic dams.

“Iran’s release of water from the Karkheh, Alvand, Karun, and Sirvan rivers into Iraqi territory has been reduced to zero,” Iraqi Water Resources Minister Mehdi Rashid al-Hamdani said in July.

This week, the ministry condemned Tehran officials for allegedly ignoring Baghdad’s requests for discussions on the water tensions between the two neighboring countries.