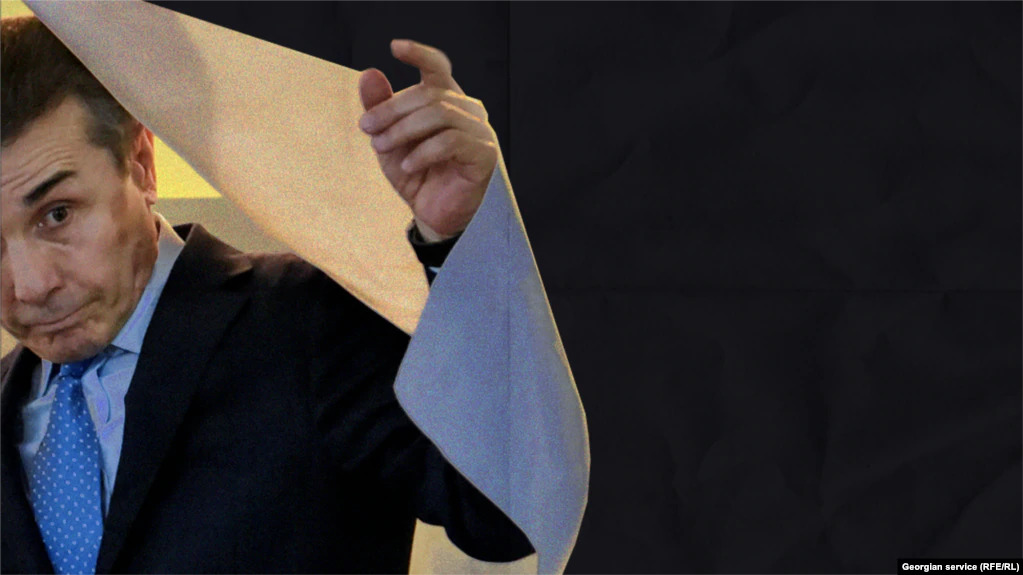

TBILISI — Former Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili announced on January 11 that he was stepping down as the chairman of Georgian Dream and will quit the party.

Proclaiming that he’d accomplished his “mission,” Ivanishvili said, “I have decided to completely withdraw from politics and let go of the reins of power.”

He said the fact he will turn 65 next month also was a factor in his decision.

But few in the Georgian capital are taking Ivanishvili’s announcement at face value.

One reason is because it is not the first time Ivanishvili has announced his retirement from politics in the former Soviet republic.

In November 2013, when Ivanishvili voluntarily stepped down as prime minister after just 13 months in office, he also said that he was quitting the political arena.

Then, in 2018, Ivanishvili announced his formal return. He was promptly elected to serve again as chairman of Georgian Dream.

In the meantime, all four men who’ve served as prime minister since Ivanishvili quit that post have been party colleagues — including current Prime Minister Giorgi Gakharia. And critics accuse Ivanishvili of having continued to govern the country from behind the scenes.

They also accuse Ivanishvili of being close to the Kremlin, something Ivanishvili denies.

According to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, Ivanishvili is the richest man in Georgia with an estimated wealth of about $5.7 billion.

He made his fortune during the 1990s by building up a collection of iron-ore producers, steel plants, banks, and real-estate properties in post-Soviet Russia — selling off most of those assets from 2003 to 2006 and the remainder in the run-up to his election as Georgian prime minister in October 2012.

He created the Georgian Dream party in April 2012.

Sources familiar with the inner workings of the party tell RFE/RL it is virtually impossible for Ivanishvili to relinquish his political power — regardless of his formal position or membership in the party.

Ghia Khukhashvili, a former adviser to Ivanishvili, said the Georgian Dream’s governing structure is designed so that “all roads lead to Ivanishvili.” Consequently, Khukhashvili says, even if Ivanishvili sincerely wants to leave politics, it will be difficult for him to do so without the collapse of that party system.

Political tensions have been high in Georgia since the official results of parliamentary elections on October 31 showed Georgian Dream maintaining its grip on power.

The opposition — led by the United National Movement (ENM) and European Georgia, plus six other parties that won parliamentary representation — claims the vote was rigged. Thousands of opposition demonstrators have taken to the streets of Tbilisi to protest the official election results.

Georgian Dream has rejected its demand for new elections, insisting the vote was free and fair.

The OSCE’s international election-observation mission concluded that the vote was “competitive and, overall, fundamental freedoms were respected,” although it cited “pervasive allegations of pressure on voters and blurring of the line between the ruling party and the state.”

In his January 11 announcement, Ivanishvili said he was “heartbroken that a constructive opposition has not been formed” in Georgia.

“I will not hide it and I will honestly say that at the end of my political career, one of the things that makes me grieve is that a state-minded and responsible opposition has not been formed yet” that would help Georgia “meet the standards of European parliamentary democracy.”

Ghia Nodia, a political analyst who heads the Tbilisi-based Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy, and Development, told RFE/RL that he doubts Ivanishvili’s sincerity.

“This is complete hypocrisy,” said Nodia, who served as Georgia’s minister of education and science in 2008. “Ivanishvili wants his favorite opposition, which has not appeared before. It is clear that he considers the United National Movement as an enemy. His attitude is similar to those parties that are also critical of the National Movement.”

Nodia accused Ivanishvili of failing to “recognize any opposition party as a legitimate player.”

“Ivanishvili wants to present himself as a democrat who is not fundamentally opposed to the opposition. But he does not want such an opposition,” Nodia said. “He wants to control the opposition as he had controlled Georgian Dream when he left the first time.”

David Zurabishvili, a former member of the Georgian parliament who used to lead the opposition Democratic Front faction, said the threat posed to Ivanishvili’s interests by the current opposition isn’t the only reason he will not be able to fulfill his “dream of leaving” politics.

“He will not go anywhere, of course, and he will not leave either,” Zurabishvili said. “Ivanishvili’s goal has always been to be able to do whatever he wants without hindrance. This means his business, infrastructure projects, and all that require control of state institutions.

“He cannot leave politics,” Zurabishvili said. “The political leadership may decide otherwise. The legislation may be different [and unfavorable to him]. But the man does not know where he wants to build or move. He has to run to get permits every time. So he cannot relinquish full control and, in principle, remain as an informal ruler as he was before. I am absolutely sure of that.”