This trend came to an abrupt stop on Thursday, with the Court’s decision in Jones v. Mississippi that judges do not need to find a juvenile murderer to have a hope of rehabilitation before sentencing them to die in prison.

This week, a truly terrible decision came down from the Supreme Court in the case of Jones v. Mississippi, which affects a court’s ability to sentence a minor to life without parole.

Previously, the court had ruled that mandatory sentences of life without parole for a minor were a violation of the 8th Amendment (being cruel and unusual punishment), and that that sentence could only be issued in extreme cases as determined under a separate assessment.

What this new ruling did was to do away with the need for that separate assessment, making life without parole an option for minors, just so long as it wasn’t mandatory—basically leaving it up to the individual discretion of a sentencer.

A punishment of life without the possibility of parole is something that arguably should not even exist for juveniles, and this ruling does away with the limitations that were at least in place around it.

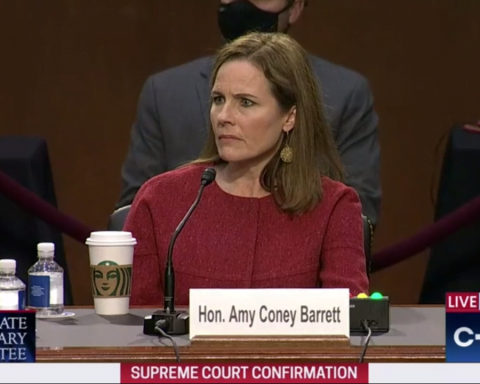

As Justice Sonia Sotomayor highlights in her dissent, not only does this new ruling step on the fairly recent precedent set, but in his majority opinion, Brett Kavanaugh pretends that precedent doesn’t even exist.

Sotomayor said Kavanaugh, along with the other conservative justices who ruled in favor here, “rewrites [the case of precedence] Miller and Montgomery to say what the Court now wishes they had said, and then denies that it has done any such thing. The Court knows what it is doing.”

“It admits as much,” she adds, accusing the justices of “burying” that precedent as a mere footnote and “[urging] lower courts to simply ignore Montgomery going forward.”

“The Court is fooling no one,” Sotomayor writes.

Most stunning, however, is the manner in which the Court got there, by casting aside years of precedent with the stroke of a pen.

Yesterday’s decision was a frightening reminder of how easily the Court can speak out of both sides of its mouth: claiming fidelity to its own past decisions, while simultaneously gutting them.

Courts are governed by the doctrine of stare decisis, Latin for “to stand by things decided.” In short, stare decisis is the fundamental doctrine that precedent matters, and that a court will stand by its rulings on issues previously brought before it.

As the Supreme Court has said, stare decisis “promotes the evenhanded, predictable, and consistent development of legal principles, fosters reliance on judicial decisions, and contributes to the actual and perceived integrity of the judicial process.” Such predictability is critical for helping the public understand what its rights are.

Put another way, in plain language, stare decisis isn’t just a legal expression of if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, but more like it ain’t broke, and moreover, our role as its stewards demands that we ensure that it be respected and protected.

This basic backdrop makes the court’s decision in Jones so perplexing. Since 2005, a series of Supreme Court rulings have methodically addressed questions of how youths can be sentenced for serious crimes.

In 2005, the Court ruled that juveniles cannot be sentenced to death. In 2010, it banned the use of life without parole for juveniles not convicted of homicide.

Two years later, it ruled in Miller v. Alabama that mandatory life without parole sentences for minors violate the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Finally, in 2016, the Court found that its ruling in Miller could be applied retroactively.

The Court’s decision in Jones broke this pattern in dramatic fashion. In the case, a 6-3 majority, led by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who wrote for the majority, found that judges need not specifically find a juvenile defendant “permanently incorrigible” — beyond redemption — before sentencing him to life in prison.

Brett Jones, convicted of the 2004 stabbing death of his grandfather after an argument when Jones had just turned 15, was challenging a mandatory sentence of life without parole imposed in Mississippi.

This decision to refuse to impose restrictions on the ability of states to sentence juveniles to life without parole was a clear break from the Court’s history, couched in language suggesting, wrongly, that the nation’s highest Court wasn’t the right venue to decide such issues.

Jones “articulates several moral and policy arguments for why he should not be forced to spend the rest of his life in prison,” Kavanaugh wrote, but “our decision allows [him] to present those arguments to the state officials authorized to act on them, such as the state legislature, state courts, or Governor.”

In effect, it’s a sad tale, but not our problem.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor was not having it, writing a withering dissent that accused the majority of turning its back on decades of precedent governing both sentencing minors, and how the Court ought to follow its past decisions.

While acknowledging the heinous nature of the crime, Sotomayor outlined Jones’ history of suffering abuse and neglect and noted his lack of access before the murder to drugs he took for mental health purposes.

Even in spite of a growing bipartisan consensus, there is a persistent strain of conservative thought that continues to cling to the past on matters of criminal justice. The majority in Jones was carrying out a political victory for many, by enshrining in law the belief that anything that makes it easier to put people in jail and keep them there has to be a good thing.

The United States stands alone as the only country in the world that sentences people to life without parole for crimes committed during their youth.

The United States is one of only about 50 nations in the world that continues to have a death penalty, placing it in the esteemed company of places we regularly criticize for their human rights records, including China, Iran, North Korea and Saudi Arabia.

The United States dwarfs virtually every other nation on the planet with its incarceration rate. The ship sailed long ago on the question of whether America has a humane system of punishment.

However, it is the Supreme Court’s caprice, and the fragility of its precedents, that should give us all pause. Despite everything the Court might say about the power of precedent, they made clear this week that their past decisions only matter until they don’t.