Official turnout in the June 18 election was 48.8 percent, the lowest ever registered in the Islamic republic, which was established in 1979. In the capital, Tehran, only 26 percent of registered voters decided to participate.

By comparison, the turnout in the last two presidential elections — in 2013 and 2017 — was about 73 percent, while in 2009 nearly 85 percent of voters cast their ballots, according to official Interior Ministry statistics.

Low Turnout, Most Invalid Votes

The number of spoiled ballots in last week’s presidential vote was 3.7 million — or about 12 percent of the total. That suggests that many people cast protest votes despite a fatwa by Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei banning blank votes “if they result in the weakening of the Islamic establishment.” In previous elections, an average of about 2 percent of the votes were invalid.

Analysts say the message is loud and clear: Iranians have signaled their discontent to their leaders through an unprecedented election boycott.

“The historically low voter turnout plus the over 3 million void votes has been first and foremost a resounding rejection of the entire establishment — hard-line or moderate — by a majority of Iranians,” Ali Fathollah-Nejad, a scholar affiliated with the Free University of Berlin, told RFE/RL.

Many had said they would boycott the vote to protest the highly restricted choice of candidates. Others were unhappy with a deteriorating economy that has been crushed by U.S. sanctions and years of mismanagement, as well as state repression that includes the brutal 2019 crackdown on anti-establishment protests. Still others cite the unfulfilled promises by politicians to bring change.

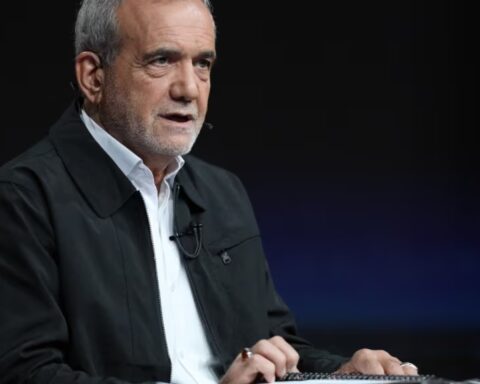

Hard-line cleric and judiciary chief Ebrahim Raisi received 62 percent of the vote in the June 18 election, in which only seven men, including two unknown moderates, were allowed to run. Three candidates dropped out of the race a day before the vote.

A Quasi-Referendum

“The real winner has been the boycott campaign that wanted to strip the Islamic republic of its ability to leverage voter turnout as proof of its legitimacy, especially to the outside world,” Fathollah-Nejad added. “What it got instead is a quasi-referendum against it.”

In Tehran, analyst Abbas Abdi said the spoiled ballots should not be counted as part of the vote, which he said would bring the turnout to around 43 percent. He suggested that a segment of those who cast invalid ballots were people who wanted to vote in the city-council elections held the same day as the presidential vote, but refused to vote for one of the four men running for president.

“Some [ in this group] voted correctly and wrote the name of one of the four [presidential candidates]. Some voted blank or wrote irrelevant names or phrases on the ballot…and threw it in the ballot box, and some put it in their pockets or tore it up,” he said.

Writing in the daily Hamshahri, sociologist Taghi Azad Armaki suggested that among those who cast invalid votes were people who still believe in voting but felt none of the candidates could represent them. “These citizens actually want a new candidate. They have practically crossed the reformist-fundamentalist dichotomy with invalid votes,” he wrote.

A Defeat For Reformists

The low turnout is widely seen as a defeat for those reformists who attempted to gather support for the only moderate candidate in the race, banker Abdolnaser Hemmati, who came in third with only 2.4 million votes. Those reformers called on Iranians to vote to preserve “the republican element” of Iran’s political system.

But as Tehran-based professor Sadegh Zibakalam noted, people turned their back on the reformists, who are seen as having failed to bring meaningful change to the country. “It’s not the government that took the message that the people are no longer with you, the reformists also took the message that people are no longer with you,” Zibakalam said at an online discussion organized by the Atlantic Council on June 20.

Khamenei turned a blind eye to the dismal turnout, praising what he described as the “enthusiastic and epic” people’s presence in the vote, while President-elect Raisi, whose path to the presidency was paved by the strict vetting of prominent moderates, said his win was “epic” and that Iranians had made an “extensive and meaningful” presence in the vote despite the deadly coronavirus pandemic and the “enemy’s psychological warfare.”

Cause For Alarm

Many warned that growing disillusionment and hopelessness was a cause for alarm and a potential recipe for future instability if the authorities fail to respond to the people’s grievances.

Former reformist President Mohammad Khatami said the low turnout and the high percentage of invalid votes was “a sign of people’s frustration and despair and their distance from the establishment that should alarm everyone.”

Khatami, who voted in the presidential election, said he bowed to all those who boycotted the vote because of “the feeling of insult to their intelligence and their rights” or due to a lack of hope for any improvement in society.

The conservative daily Jomhuri Eslami called for action from the government. “The Islamic establishment must act in order not to lose the support of the people,” it said, and that those who believe in the system cannot be indifferent to “the bitter reality.”

The lowest turnout in a presidential election follows a record low turnout in the parliamentary elections held last year. There was also a high number of invalid ballots cast and another low turnout for the Tehran-city council elections, with the number of spoiled votes almost equaling the number garnered by the top candidate in the race.