Brookings – In recent years three American presidents, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joseph Biden, have confronted a crisis in Yemen which centers around a Saudi-led military intervention against a radical insurgent group that controls most of northern Yemen. John F. Kennedy was the first American president to confront a serious international crisis in Yemen, coming virtually at the same time as he faced the Cuban missile crisis with the Soviet Union and the Chinese invasion of India in the autumn of 1962. Kennedy did something very rare in America’s dealing with Yemen: He disregarded Saudi appeals to support their covert war in Yemen and instead sought to be a peacemaker. Kennedy’s policy offers a significant alternative to the failed approach of the last six years.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen was increasingly caught up in the political turmoil sweeping the Middle East. (Throughout the Cold War, the modern country of Yemen was divided into North Yemen, centered around Sana’a and the focus of this essay, and a south centered around the port of Aden, controlled by the British into the 1960s and by the communist People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen from 1967 on). At the center of the turmoil was Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. Nasser had led Egypt’s own revolution in 1952 that deposed its monarchy. He became president in 1954 and set up a progressive nationalist regime which threw out the British, nationalized the Suez Canal and fought Israel, Great Britain, and France in 1956. He was the spokesman for pan-Arabism, the notion that there should be a single united Arab state from Morocco to Oman. In 1958 Syria united with Egypt to form the United Arab Republic (UAR) and the dream of Arabism seemed to be within reach.

The UAR also aligned itself with the Soviet Union and purchased arms from the Soviets. This injected the Cold War into the region. In 1957, U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower promised to aid any country under threat from communism and in 1958, after the UAR merger, he sent troops to Lebanon to prevent a Nasserist takeover of the country. Britain sent paratroopers to Jordan to keep King Hussein in power.

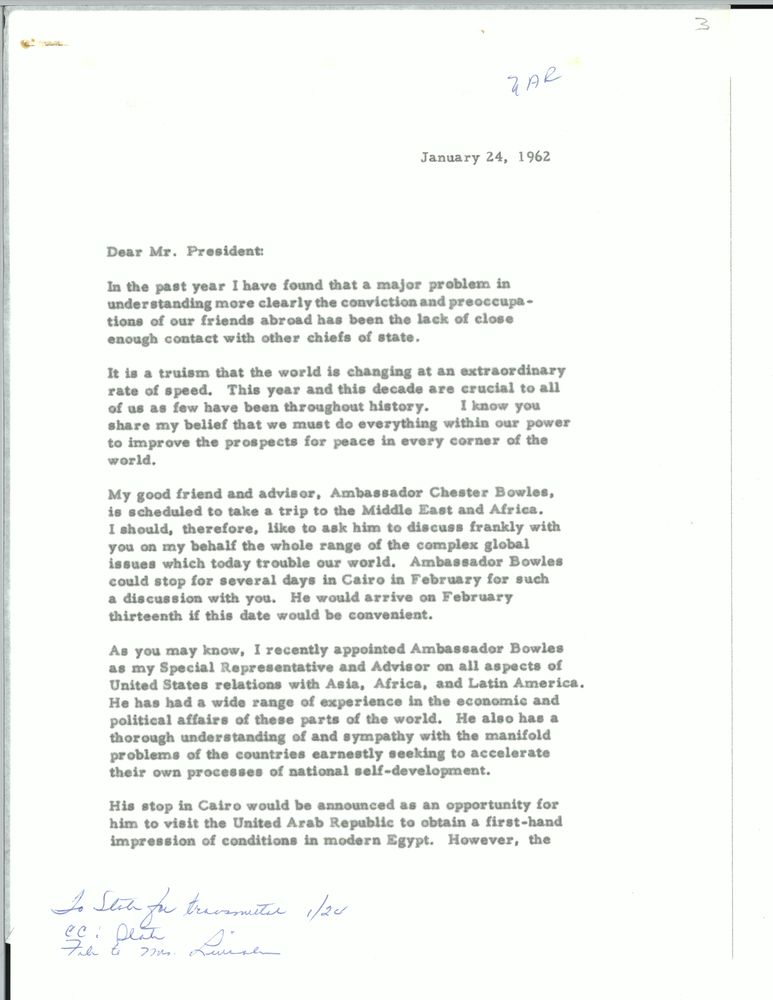

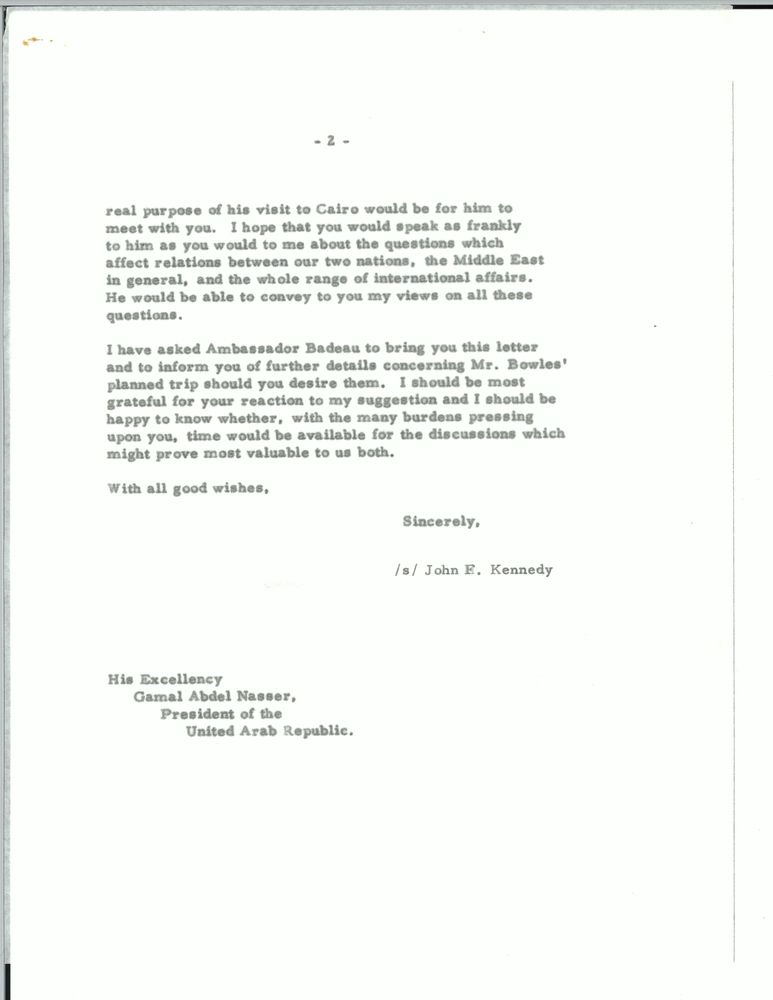

Kennedy came into office determined to deal with Arab nationalism as a phenomenon America had to work with, not fight. He had been the first U.S. senator to call for Algerian independence and for the U.S. to cease backing the French army trying to repress the independence movement. In office, Kennedy reached out to Nasser and engaged him in a long series of letters about the Middle East, trying to develop a useful dialogue.

The Yemeni monarchy tried to appease Nasser by affiliating the country with the UAR under a formulation calling the UAR and Yemen the “United Arab States” (UAS). It also invited Egypt and the Soviet Union to set up training programs for its army. The UAS collapsed in 1961 when Syria left the bloc and regained its independence. Egypt withdrew its advisors from Yemen, but the Soviets remained. Nasser began plotting to dispose the Yemeni monarchy with the goal of securing a foothold on the Arabian Peninsula that could be a base to overthrow the Saudi monarchy and seize the strategic port of Aden from the British.

The coup, Egypt, and the Soviet Union

On September 19, 1962, 71-year-old Imam Ahmed bin Yahya died in his sleep. He had ruled since his father’s death in 1948. His son, 36-year-old Muhammad al-Badr ascended to the throne. A week later the army attacked the royal palace and created the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR). Badr fled into the countryside, many thought he was dead. Egypt immediately recognized the new state. Loyalists to Badr fought back in the countryside.

Egypt and Russia moved quickly to back the new Yemen Arab Republic. The principal driver of the Egyptian intervention was Anwar Sadat, the speaker of the National Assembly and Nasser’s ultimate successor, who argued it was a way to restore the momentum toward Arab unity after the Syrian withdrawal from the UAR. It would also offer a base for operations against Saudi Arabia and Aden. The Egyptian intervention was code named Operation 9000.1

Moscow was equally swift to move. The Soviet Union recognized the new Yemeni government on October 1, 1962, the first non-Arab state to do so. The Soviets already had a substantial presence in country. In addition to providing military advisers, they had built a modern harbor and port infrastructure in Hodeida in the late 1950s which soon became the gate way for Egyptian troops to enter the country. Moscow’s ally, the People’s Republic of China, had built the highway linking Hodeida to Sana’a. In the first year of the war, Egypt used 18 ships to make 122 deliveries of supplies to Yemen.

But the immediate requirement was an airlift of troops, weapons, and other material to Sana’a to bolster the republicans against the counterrevolutionary royalist forces. On September 26, 1962 Nasser and Sadat asked the Soviets to help. Nikita Khrushchev responded by sending 10 large Antonov An-12 heavy-lift aircraft to Egypt with Soviet crews. The first flight arrived in Sana’a on September 30.

Moscow’s support went beyond the airlift. Beginning in late October (at the climax of Cuban missile crisis and the Chinese invasion of India), Soviet Tupolev Tu-16 twin engine bombers began bombing royalist targets along the Saudi-Yemeni border. The Tu-16 were also flown by Soviet crews. The operation was code named Mubarak after Hosni Mubarak (Sadat’s eventual successor as Egyptian president) who was the nominal Egyptian commander of the Tu-16 squadron. In early October four Soviet advisors were captured by the royalists near the city of Marib, the royalists sent them to the British in Aden who then repatriated them to Moscow.

Kennedy was closely monitoring the situation. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) provided him with a daily written summary of its Top Secret intelligence called the President’s Intelligence Checklist or PICL (later known as the President’s Daily Brief or PDB). Declassified PICLs for the fall of 1962 are available on the CIA’s website, arranged by date. Especially in late September and October, three stories dominated: Cuba, India, and Yemen. The day after the coup the CIA reported that Badr’s uncle Hasan was rallying the northern Zaydi Shia tribes along the Saudi border to fight to restore the monarchy. The next day it identified the leader of the coup as Brigadier General Abdullah al-Sallal, the commander of the imam’s bodyguards. The brief said Cairo was “delighted” over the coup and was complicit in its occurrence. The agency reported that Sallal and other senior coup plotters were members of the Egyptian-backed Free Yemeni Movement.

Kennedy was told by the intelligence on October 2, 1962 that “a civil war is shaping up with direct backing from the UAR for one faction and from Saudi Arabia for the other.” Two Saudi pilots then defected to Egypt with their U.S.-made aircraft which were bringing arms to the royalists. It emerged that Badr had not died in the coup attempt but had successfully fled Sana’a to join the royalists in their camps in Saudi Arabia. Jordan was also providing aid to the royalists. On October 6, 1962, the President’s Intelligence Checklist reported “the struggle in Yemen is becoming international.” Five days later it told Kennedy “Soviet pilots are now flying supplies and equipment in from Cairo in AN-12 conventional transports which have a capacity for upwards of 80 combat-ready troops.”

Kennedy and Faisal

The president was pressed by Saudi Arabia and Jordan, as well as the British, to back the royalists and not recognize the new government. The CIA reported King Hussein was pressing both Washington and Riyadh to “intervene in force in Yemen before it is too late.” Hussein warned that a revolution in Saudi Arabia “could all too easily be ignited by an adventure into Yemen.” By October 31, the CIA estimated Egypt had 4,000 troops in country. That would grow to 30,000 by March 1963.2 Jordan had moved a battalion of its army to Saudi Arabia to help the royalists.

Kennedy also sent messages to Nasser, Hussein, Saudi Arabia’s King Saud, and Sallal, now president of the YAR, urging a diplomatic settlement. In Kennedy’s plan, Nasser would agree to withdraw his troops from Yemen while the Saudis and Jordanians ceased their support for the royalist rebels. The Saudis and Jordanians rejected Kennedy’s proposal since it would leave the republican government in charge. Kennedy did recognize the republican government in Sana’a on December 19, 1962 despite the Saudi, Jordanian, and British pressure not to. The United Nations General Assembly recognized the republic the next day.

Saudi Crown Prince Faisal was in New York for the annual General Assembly meeting in October. Faisal pressed Kennedy to conduct a show of force in the Red Sea to halt Egyptian arms and troops from going to Hodeida. Kennedy demurred from intervening. On October 5, 1962 he met with the prince in the White House, including a private one-on-one meeting in the family quarters of the building, a highly unusual honor for a foreign visitor. They agreed that the United States would publicly reaffirm its commitment to preserve the independence and integrity of Saudi Arabia and would step up port visits by the U.S. Navy to Saudi ports and increase training U.S. for Royal Saudi Air Force personnel.3

But Kennedy also made it clear to the crown prince that he believed the most serious threat to the survival of the House of Saud came from within the country. Unless Saudi Arabia took steps to modernize, Kennedy believed the monarchy was doomed. In the private one-on-one, Faisal promised to abolish slavery in Saudi Arabia, begin woman’s education, and end arbitrary arrest and confinement. It was an extraordinary and unique moment in America’s relationship with the kingdom, the only time an American president has intervened successfully in the kingdom’s internal affairs.

Faisal made a deep impression on the president, in contrast to his incompetent brother King Saud whom he would oust in November 1964 with the Royal Guards, literally at sword point.4 Saud moved to Cairo at first and then exile in Greece. Kennedy found Faisal to be trustworthy and enlightened. He was also a profoundly pious man.

At the height of the Cold War, the Soviet Union led by Nikita Khrushchev was directly intervening in a civil war in Yemen that threatened the survival of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, America’s oldest partner in the Arab world. Unlike in Cuba, the Soviets in Yemen with their Egyptian partners did not back down but rather escalated the conflict.

The covert war

Concerned about the likely revolutionary spill over from Yemen to Aden, the British set up a secret organization run out of a building on Sloane Street in London to help arm and train the royalists. The British would recruit mercenaries — many from Belgium and France with experience in counterinsurgency from Algeria and Vietnam — to assist the royalists, Saudis, and Jordanians in fighting the republicans, Egyptians, and Soviets.

Israel, which had its own differences with Nasser, joined in the clandestine campaign. The royalists reached out to Israeli diplomats in Europe. Badr sent a representative to Tel Aviv to ask the Israeli secret intelligence service, the Mossad, for help. The Mossad sent an operations officer to Yemen to coordinate on the ground with the royalists. In the next few years, the Israeli Air Force flew over Saudi Arabia to drop supplies of weapons to the royalists with the Saudi’s knowledge and approval. Nahum Admoni was the Mossad officer in charge of Operation Rotev (“gravy”); he would go on to become the Mossad’s director in the 1980s.5

By November 1962, the CIA told Kennedy that “all our evidence indicates that the UAR, Saudi Arabia and Jordan are getting themselves more and more deeply embroiled” in the Yemen war and that several hundred Soviet soldiers were also on the ground: “Soviet involvement, directly and through the UAR, is growing.” But Kennedy kept America out of the war, ultimately recognizing the republican government of the YAR, which irritated Faisal and Hussein.

The CIA warned the president that both Saudi Arabia and Jordan were highly vulnerable to their own revolutionaries. Hussein told the U.S. ambassador in Amman, “I wonder who will be next, King Saud or me?” Both kingdoms were militarily weak. The Saudis could barely summon 5,000 combat-ready troops. The Royal Saudi Air Force had to be confined to staying on the ground because of repeated defections of plans and pilots to Egypt. The Royal Jordanian Air Force, Hussein’s pride and joy, sent six fighters to Saudi Arabia to help defend the kingdom; the squadron commander and two aircraft defected to Egypt.

President Kennedy kept up his diplomatic efforts to gain a political solution to the war. He backed efforts by the United Nations to mediate. He also sent his own emissary, Ellsworth Bunker, a distinguished American diplomat who had served as ambassador in both Italy and India. Bunker arrived in Riyadh on March 6, 1963, where Faisal reluctantly agreed to trade off ending Saudi support for the royalists in return for Egypt’s withdrawal of its troops. Bunker then met with Nasser in Beirut to gain Egyptian support. Nasser promised he would “gradually” withdraw his troops if the Saudis and others halted their aid to the royalists.

To back up his diplomacy, Kennedy did send F-100 fighter jets to Saudi Arabia in 1963 to show vividly American support for the defense of the kingdom. By then there were almost daily Egyptian airstrikes at royalist bases on the border, often in Saudi territory. Operation Hardsurface was the first-ever deployment of American combat forces to the Arabian Peninsula and began in July 1963.6 It ended shortly before Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas, Texas in November.

To oversee the situation on the ground the U.N. created an observer mission, the United Nations Yemen Observation Mission (UNYOM), led by a Swedish major general named Carl von Horn. In April 1963, von Horn went to the region where he was told by the Egyptians that in fact they had no intention of withdrawing their forces and by the Saudis that they would not halt aid to the royalists. Von Horn tried for months to get some deal, but Cairo and Riyadh were not buying diplomacy; both escalated their support for their clients in Yemen. By September 1964, the U.N. admitted failure and UNYOM was disbanded.

JFK handled the Yemen crisis coolly and prudently. He judged based on the CIA’s reporting that the royalists had more than enough foreign help from the Saudis, Jordanians, British, and Israelis; they did not need American covert assistance as well. He was also aware that the royalists were medieval in their worldview, not agents of change. He realized that the Saudi monarchy was also backward and that the biggest threat to its survival was internal, not Egyptian. Kennedy found an ally in Faisal, who wanted to modernize the kingdom to secure its survival. He kept his line of communication with Nasser open and sent high-level representatives to Cairo to meet with the Egyptians. Finally, he recognized the YAR and kept an embassy in Sana’a to provide real-time, on-the-ground reports on the situation.

LBJ, the Six-Day War, and lessons learned

The war in Yemen escalated further on President Lyndon B. Johnson’s watch. By 1966, there were 70,000 Egyptian soldiers in Yemen bogged down in a quagmire that was bankrupting Cairo. Sadat continued to push to win the war. The best of Egypt’s army was in Yemen when the Six-Day War broke out with Israel in June 1967. Israeli experts acknowledge part of the reason for Israel’s stunning success against Egypt was the distraction of men and material to Yemen. Yossi Alpher, who handled the Israel Defense Force’s role in Rotev, said later “we learned from prisoners we captured in the Sinai just how much the events in Yemen negatively impacted the mood and readiness of the Egyptian army.”7 The Yemen government broke relations with the United States on June 7, 1967, the third day of the war, to protest Johnson’s support for Israel.

The defeat in the Sinai in June led to the end of Egypt’s intervention in Yemen. Faisal and Nasser reached an agreement shortly after the Six-Day War for Saudi Arabia and Egypt to end their support to the warring parties and the Egyptians evacuated Yemen. Sallal was ousted in a coup shortly afterwards and a new republican government came to power in Sana’a. The royalists besieged the capital in November 1967, but the republicans held out and the siege lifted in February 1968. A final cease-fire ended the civil war in 1970 with a republic still in place. By then the United States was completely consumed with the war in Vietnam. Meanwhile, in 1968 Aden became independent and a Communist government with close connections to the Soviets created the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, dedicated to the overthrow of the Gulf monarchies.

Kennedy demonstrated that America can pursue a policy toward Yemen that is not in lock step with Saudi Arabia but rather independent and balanced.

Kennedy demonstrated that America can pursue a policy toward Yemen that is not in lock step with Saudi Arabia but rather independent and balanced. We would have a better chance of ending the current war in Yemen, and the horrendous humanitarian catastrophe it has created, by distancing ourselves much more from Riyadh. The Houthi rebels are no friends of America — they routinely chant death to America and Israel — but have committed few serious attacks on Americans or U.S. interests. They get assistance from Iran, but they are not Iranian puppets.

We can learn a lot from Kennedy’s Yemen crisis today. Obama, Trump, and Biden have given the Saudis diplomatic and military support for their war for seven years, but the Houthis remain in charge of Sana’a and most of northern Yemen. It is time for a different approach that calls on the Saudis to stop their war unilaterally, cease aiding the Houthis’ adversaries, end the blockade that has created a humanitarian disaster, and leave the Yemenis to sort out their political future without foreign intervention, assisted by U.N. mediators if they want.