The sudden death on April 19, 2021 of Chadian President Idriss Déby Itno is creating a very dangerous vacuum in Central Africa and the Sahel. Déby, who ruled Chad for 30 years, was killed while fighting rebels trying to overthrow his government.

Few sub-Saharan African countries have the regional reach of Chad, and this is due essentially to its army — an army Déby was visiting when he was killed in a firefight, as Chadian troops battled with rebels from Libya. Chad has one of the most effective armies in sub-Saharan Africa and has, over the last 20 years, appeared on all fronts of the war against jihadist groups in the Sahel. It has also been involved in some neighboring civil wars, notably those in Sudan and the Central African Republic (CAR), and more indirectly in Libya.

CHAD’S POWERFUL ARMY GIVES IT A FORMIDABLE FOOTPRINT IN THE REGION

Déby built Chad’s powerful army for a few reasons: to protect his regime from the constant ethnic rivalries and ambitions of various warlords from the country’s north; and also to achieve international recognition, credibility, and leverage in order to manage internal politics and use economic resources without interference. Déby always received strong backing from the West, particularly France and the U.S., despite his autocratic rule and rampant government corruption.

Chad has been the strongest supporter of Barkhane, the French military operation to fight jihadist groups in the Sahel. It has repeatedly sent expeditionary forces into the region and has just positioned more than 1,000 troops in the tri-border region of Liptako-Gourma, where a bloody jihadist insurgency is wreaking havoc on the population and national armies. Chad is also widely recognized as an essential pillar of the G5 Sahel — a military alliance between Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger, and heavily supported by France and the U.S. — to fight the region’s powerful jihadist insurrection. The Chadian army is very familiar with the terrain, as its troops were critically involved in the 2013 French-led military operation to defend Mali from a takeover by well-organized Islamic armed groups. Chad is also one of the top troop contributors to the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali, the peacekeeping operation set up in 2013 in Mali in response to the insurrection.

Chad’s military presence in the region is not limited to the Sahel. In 2015, along with troops from neighboring Niger, it played a major role in dislodging Boko Haram from Northern Nigeria. It liberated some large Nigerian cities that had been under the terrorist organization’s control for months, and struck a near-fatal blow to the organization. In doing so, it shamed the Nigerian army — one of the largest in Africa — that had been paralyzed by Boko Haram for years. Chad continues to fight Boko Haram in and around Lake Chad. Recently, it lost around 100 men in clashes with Boko Haram and one of its splinter groups, the Islamic State in the West Africa Province (ISWAP). In response, it mounted a massive offensive and destroyed the camps of these organizations, supposedly killing more than 1,000 militants. At that time, Déby complained bitterly that his army was the only one taking on militants in this region, and threatened to pause all support for the war against terrorist groups outside of his country. These threats were a recurrent strategy to remind the world of Chad’s centrality and to gain support and recognition from Western nations.

Chad also played a role in the conflict in CAR. A few years ago, it got involved with armed groups in CAR’s northeast, assembled under a loose association called Seleka that occupied part of the country. Chad played a role in ending the conflict. Following the 2013 CAR civil war, Chad participated in the U.N. peacekeeping operation, contributing 850 troops, but left after being accused of human rights abuses and of being partial to the Muslim population. The situation was further complicated by members of the Chadian army having commercial interests in CAR linked to cattle raising and trading. In CAR, the Chadian army’s role varies: Sometimes it plays a stabilizing role, and at others it clearly contributes to violence and exactions.

Déby always kept an eye on Darfur, and more broadly on Sudan — mostly for internal security reasons, but Chad also had a strong impact on its neighbor at times. His Zaghawa ethnic group (and of some of his most trusted generals) represents less than 5% of the Chadian population, but is one of the most populous groups in Darfur. Some Chadian Zaghawa people based in Darfur had long been Déby’s most vigorous armed opposition group. To manage his opponents, he made efforts to please Khartoum, while always showing that he could influence the civil war that was ravaging the west of the country through his ethnic and family connections. He did this with the Justice and Equality Movement (MJE), one of the main armed groups opposing President Omar al-Bashir. In 2005, tensions between the two countries became heated, with armed clashes at the border. Twice, armed groups coming from Sudan to overthrow Déby nearly reached the capital, N’Djamena. In response, Déby sent his troops to track the rebels and reached the suburbs of Khartoum, clearly showing that he could bring Chad’s military might to bear.

By the same logic, Déby tried to manage his relations with Libyan groups, and it is understood that he had a good relationship with General Khalifa Haftar. Today, the most active military opposition to Déby’s regime comes from southern Libya (the Fezan), where some Chadian rebels helped General Haftar and where the Goran tribe — which constitutes the majority of the rebels — are active in illicit trading activities. The group that entered Chad and ended up killing Déby last week came from southern Libya; they built up an impressive arsenal, probably through their involvement in the Libyan civil war.

A WELL-FINANCED, POWERFUL, AND UNUSUALLY-STRUCTURED ARMY

Déby’s powerful army is an interesting mix of rebel groups and a modern army, making it very powerful but also highly dependent on Déby’s personal involvement. Most of the high-ranking officers and elite troops are recruited from the northern tribes — principally the Zaghawa, but also the Goran and other groups more broadly known as Toubous. They possess very old and solid combat traditions, excellent knowledge of the desert, an astonishing physical endurance, and a lot of courage. The elite units are often comprised of family and clan members who know each other well. At the same time, the army uses well-trained technicians such as helicopter and combat plane pilots who benefit from heavy support from France and other Western countries. Oil revenues fund generous salaries for officers and elite troops, as well as an impressive arsenal of relatively sophisticated equipment, including combat aircraft and helicopters. The International Crisis Group estimates that 40% to 50% of Chad’s budget goes to the country’s defense and security expenses.

In 2000, Chad started to exploit relatively important oil reserves situated in the country’s south. Worried about corruption, the World Bank and a number of development partners set up a complex mechanism by which they would finance an essential pipeline to export the oil to the coast, on the condition that the revenue would be channeled to a special fund monitored by donors. This mechanism was set up to ensure that resources would be used for development and poverty alleviation. At that time, this mechanism was hailed as a great innovation in good governance. But starting in 2006, Déby managed to change the original system to channel significant oil revenues to his army and to large public work programs of his choice, which did not always benefit the poor. Given the regional geopolitics, however, Western donors averted their eyes and accepted the situation.

MANY INSTABILITY RISKS THAT NEED CAREFUL MANAGEMENT

Despite its strength, the Chadian army also has significant weaknesses that could feed instability. First, the way the army acts toward the civilian population, with frequent exactions, limits its capacity to build up trust in ways that are essential for stability. Second, the army is marred by internal rivalry between commanders. Family rivalries or clan-based rivalries often extend inside the army. The fact that so many of the elite soldiers are northerners means that they also tend to have strong connections to some of the rebel movements based in Sudan or Libya, which are often comprised of former soldiers of the Chadian army. Also, Déby’s strong involvement in the army — which he often commanded directly in the field — is probably the biggest risk. He kept the army’s internal cohesion through personal negotiations, meaning that many loyalties are to him and not to other high-ranking officers.

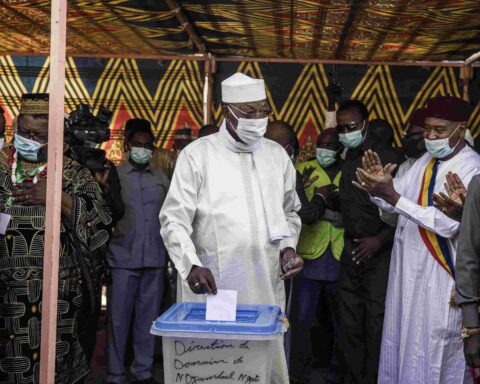

An additional source of instability is Chad’s tense and fragmented political landscape. Just days before his death, Déby was reelected for a sixth consecutive term, with 80% of the vote; however, his hold on power was largely seen as a parody of democracy. His regime was autocratic, and while a decade ago he was making efforts to accommodate opponents and had some pretense of inclusiveness, his regime is now opaque, with most decisions made by a small group of friends and relatives. Just after his death, a Transitional Military Council was established, with 15 generals all very close to Déby; it is chaired by his son, a 37-year-old general.

The council has suspended the constitution and declared an 18-month transition period. One of the main reasons for the move is certainly the fear that the army could disintegrate, but it is also to ensure that the clan of Déby keeps control of the army and the country. The political opposition and civil society have called the move a military coup and called for protests, as did the African Union. Neither France nor the U.S. said anything immediately, but after protesters died during demonstrations, they weighed in with condemnation of the killing.

These are very delicate times for Chad and the entire region. The personalization of Déby’s regime has left the country with extremely weak institutions. There is a real risk of serious infighting inside the army and the circles of power, even inside Déby’s own family. Also, tensions with the political opposition are rapidly increasing. It seems clear that suspending the constitution will only make things worse. France, the European Union, and the U.S. — the main donors to Chad — should put strong pressure on the Transitional Military Council so that it engages in a more substantive dialogue with political factions and civil society than it has done so far. The council should also show that it is serious about organizing elections, as it said it would, much earlier than in 18 months, as announced. Under pressure, the council has just nominated a civilian prime minister. This is a good step. It should also nominate a government sufficiently representative of the country’s different social groups, particularly ethnic groups from the south and center that have been marginalized. It would also be important for Western nations to pressure the new Libyan authorities, particularly General Haftar, to rapidly improve their control of various militias and armed groups in Libya. The ceasefire in this country has created opportunities for highly armed groups to look for opportunities abroad, as was the case when the Gadhafi regime fell.