Growing numbers of religious and political leaders are embracing the “Christian nationalist” label, and some dispute the idea that the country’s founders wanted a separation of church and state.

On the other side of the debate, however, many Americans – including the leaders of many Christian churches – have pushed back against Christian nationalism, calling it a “danger” to the country.

Most U.S. adults believe America’s founders intended the country to be a Christian nation, and many say they think it should be a Christian nation today, according to a new Pew Research Center survey designed to explore Americans’ views on the topic. But the survey also finds widely differing opinions about what it means to be a “Christian nation” and to support “Christian nationalism.”

For instance, many supporters of Christian nationhood define the concept in broad terms, as the idea that the country is guided by Christian values. Those who say the United States should not be a Christian nation, on the other hand, are much more inclined to define a Christian nation as one where the laws explicitly enshrine religious teachings.

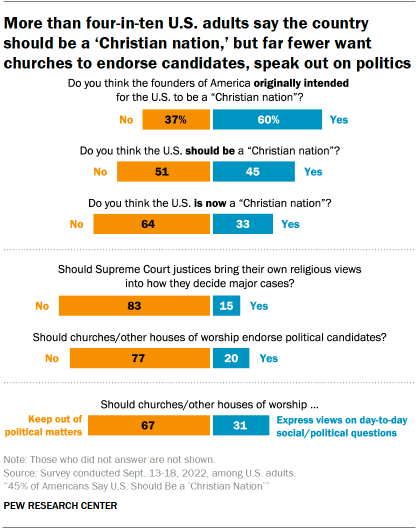

Overall, six-in-ten U.S. adults – including nearly seven-in-ten Christians – say they believe the founders “originally intended” for the U.S. to be a Christian nation. And 45% of U.S. adults – including about six-in-ten Christians – say they think the country “should be” a Christian nation. A third say the U.S. “is now” a Christian nation.

At the same time, a large majority of the public expresses some reservations about intermingling religion and government. For example, about three-quarters of U.S. adults (77%) say that churches and other houses of worship should not endorse candidates for political offices. Two-thirds (67%) say that religious institutions should keep out of political matters rather than expressing their views on day-to-day social or political questions. And the new survey – along with other recent Center research – makes clear that there is far more support for the idea of separation of church and state than opposition to it among Americans overall.

This raises the question: What do people mean when they say the U.S. should be a “Christian nation”? While some people who say the U.S. should be a Christian nation define the concept as one where a nation’s laws are based on Christian tenets and the nation’s leaders are Christian, it is much more common for people in this category to see a Christian nation as one where people are more broadly guided by Christian values or a belief in God, even if its laws are not explicitly Christian and its leaders can have a variety of faiths or no faith at all.

Some people who say the U.S. should be a Christian nation are thinking about the religious makeup of the population; to them, a Christian nation is a country where most people are Christians. Others are simply envisioning a place where people treat each other well and have good morals.

Combining the results of the new survey with an earlier Center survey on the relationship between religion and government conducted in March 2021 helps to show the distribution of these differing viewpoints. Thousands of respondents took both surveys, so it is possible to see how they answered multiple questions.

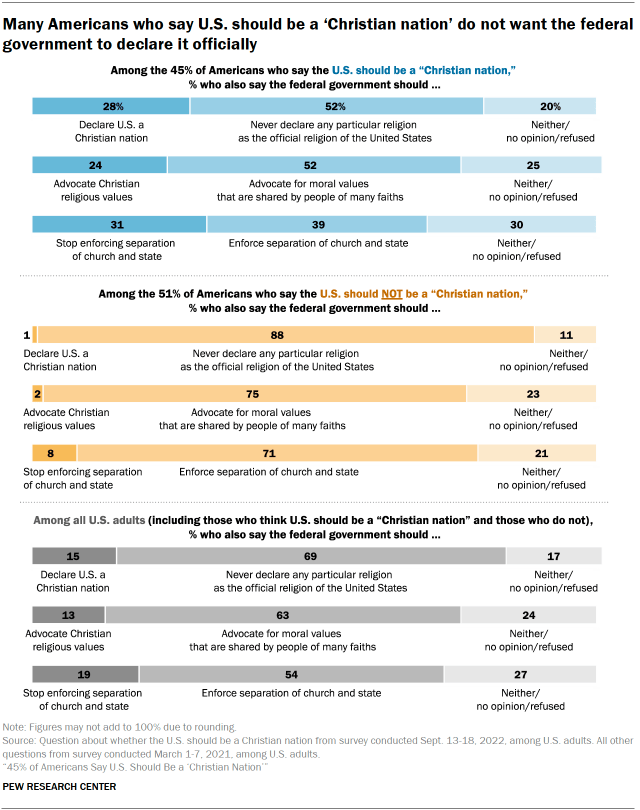

Among those who say the U.S. should be a Christian nation, roughly three-in-ten (28%) said in March 2021 that “the federal government should declare the U.S. a Christian nation,” while half (52%) said the federal government “should never declare any particular religion as the official religion of the United States.”

Similarly, among those who say in the new survey that the U.S. should be a Christian nation, only about a quarter (24%) said in the prior survey that the federal government should advocate Christian religious values. About twice as many (52%) said the government should “advocate for moral values that are shared by people of many faiths.”

And three-in-ten U.S. adults who want the U.S. to be a Christian nation (31%) said in the March 2021 survey that the federal government should stop enforcing the separation of church and state. More took the opposite position, saying the federal government should enforce that separation (39%).

At the same time, however, people who believe the U.S. should be a Christian nation are far more inclined than those who think it should not be a Christian nation to favor officially declaring Christianity to be the nation’s religion, to support government advocacy of Christian values, and to say the government should stop enforcing separation of church and state.

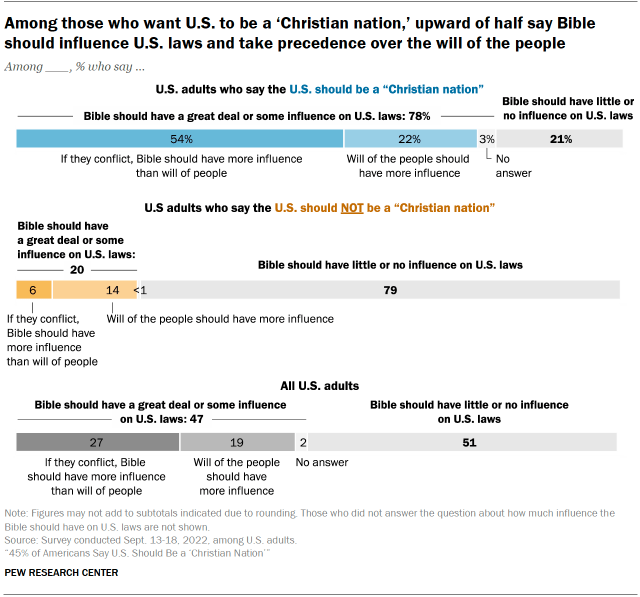

Furthermore, the new survey finds that nearly eight-in-ten people who say the U.S. should be a Christian nation also say the Bible should have at least some influence on U.S. laws, including slightly more than half (54%) who say that when the Bible conflicts with the will of the people, the Bible should prevail.

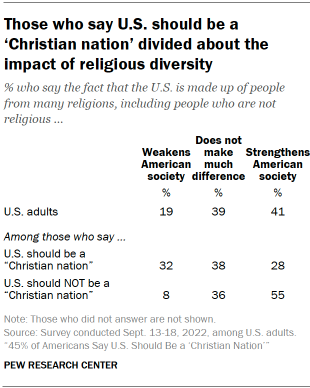

And about a third of U.S. adults who say the U.S. should be a Christian nation (32%) also think the fact that the country is religiously diverse – i.e., made up of people from many different religions as well as people who are not religious – weakens American society. Those who want the U.S. to be a Christian nation are far more inclined than those who do not want the U.S. to be a Christian nation to express this negative view of religious diversity.

Still, among those who say the U.S. should be a Christian nation, there are roughly as many people who say the country’s religious diversity strengthens American society as there are who say it weakens society (28% vs. 32%).

And cumulatively, the survey’s results suggest that most people who say the U.S. should be a Christian nation are thinking of some definition of the term other than a government-imposed theocracy.

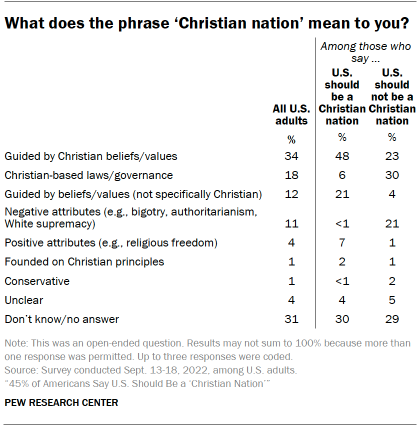

Indeed, in response to a question that gave respondents a chance to describe, in their own words, what the phrase “Christian nation” means to them, nearly half (48%) of those who say the U.S. should be a Christian nation define that phrase as the general guidance of Christian beliefs and values in society, such as that a Christian nation is one where the population has faith in God or Jesus Christ, specifically. Fewer people who say the U.S. should be a Christian nation explain that they mean the country’s laws should be based on Christianity (6%).

Those who say the U.S. should not be a Christian nation are much more likely than those who say it should be one to say that being a Christian nation would entail religion-based laws and policies (30% vs. 6%). Others who oppose Christian nationhood use negative words to describe the concept, such as that a Christian nation would be “strict,” “controlling,” “racist,” “bigoted” or “exclusionary” toward people of other faiths (21%). (For additional discussion and details of the results of the survey’s open-ended question about the meaning of the term “Christian nation,” see Chapter 3.)

In your own words, what does the phrase ‘Christian nation’ mean to you?

Examples of responses among those who say …

… the U.S. should be a Christian nation

- “A country based on Christian beliefs. Freedom of religion, all men being created equal. While belief in the 10 Commandments would be great, imagine life in the U.S. if only four to 10 were kept! People need to believe in something/someone higher than themselves.”

- “Belief in the underpinning philosophy of Judeo-Christian traditions, which includes loving thy neighbor, belief in service to a higher power than yourself, individualism, free will and traditional morality.”

- “Attributing all that we have to God or a supreme being.”

… the U.S. should NOT be a Christian nation

- “‘Christian’ used to be code for polite and decent; now it’s code for the opposite. A ‘Christian nation’ would be intolerant, inflexible and ultimately brutal.”

- “I don’t like that term, but to me it means theocracy. I realize other people mean it in different ways, such as to refer to the fact that most people in America are Christian. But to pretend that the nation somehow belongs to Christians just because they happen to be the majority excludes everyone else.”

- “A White Christian ethno-state.”

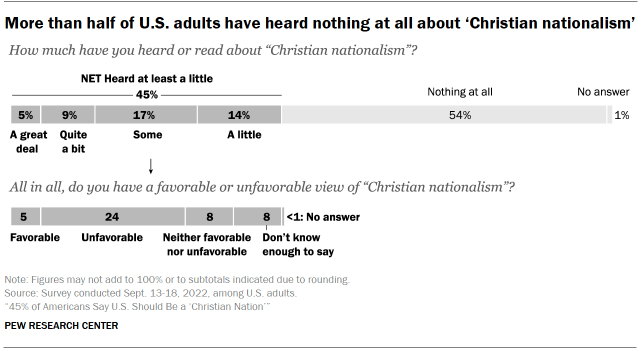

In addition to the questions that asked about being a “Christian nation,” the survey asked other respondents about their familiarity with the term “Christian nationalism.”1 Overall, the survey indicates that more than half of U.S. adults (54%) have heard nothing at all about Christian nationalism, while 14% say they have heard a little, 17% have heard some, 9% have heard quite a bit and 5% have heard a great deal about it.

Altogether, 45% say they have heard at least a little about Christian nationalism. These respondents received a follow-up question asking whether they have a favorable or unfavorable view of Christian nationalism. (Those who said they had heard nothing at all about the term were not asked for their opinion on it.) Far more people express an unfavorable opinion than a favorable one (24% vs. 5%), though even among respondents who say they have heard at least a little about Christian nationalism, many don’t express an opinion or say they don’t know enough to take a stance.

In an open-ended question asking about the meaning of “Christian nationalism,” upward of one-in-ten Americans say the term implies some form of institutionalization or official dominance of Christianity, such as theocratic rule or a formal declaration that the U.S. is a Christian nation with Christian inhabitants. At the same time, many Americans who say they hold a favorable view of Christian nationalism describe it in ways that suggest it promotes morality and faith without necessarily being in a position of formal, legal dominance. Overall, however, Americans’ descriptions of Christian nationalism – especially among those who have an unfavorable opinion of it – are more negative than positive. (See an accompanying interactive feature for a selection of responses to this question.)

These are among the key findings of a new Pew Research Center survey, conducted Sept. 13-18, 2022, among 10,588 respondents who are part of the Center’s American Trends Panel. The survey is the latest entry in the Center’s long-running effort to gauge the public’s perceptions and attitudes related to religion in public life – including their views about how much influence religion has in American society and how much it ought to have. The survey also contained several questions about religion and the Supreme Court.

The high court’s last session produced a number of decisions with implications for religion, including the historic case that overturned Roe v. Wade as well as rulings that favored a high school football coach who led Christian prayers after games and allowed public funding for private religious schools.

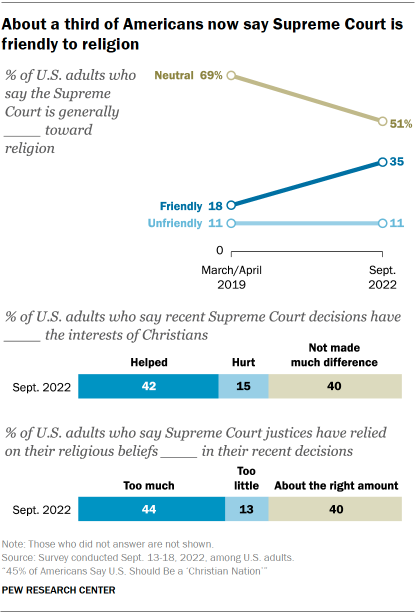

The new survey finds a big jump in the share of Americans who say they think the Supreme Court is friendly toward religion. Today, roughly a third of U.S. adults (35%) say the court is friendly to religion, up sharply from 18% who said this in 2019, when the Center last asked this question.

About four-in-ten U.S. adults (42%) say the Supreme Court’s recent decisions have helped the interests of Christians in the United States, compared with 15% who say they have hurt Christians. And 44% of U.S. adults say Supreme Court justices have relied on their religious beliefs too much in their recent decisions, versus 13% who say they have relied on these beliefs too little. Both of these questions were asked for the first time as part of the new survey.

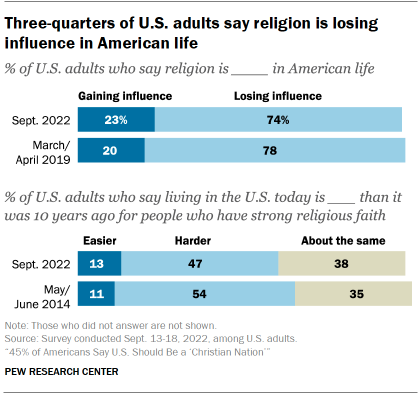

The survey also finds a small but noticeable uptick in the share of respondents who say religion is gaining influence in American life – from 20% in 2019 to 23% today. And the share of Americans who say it has become harder to be a person of strong religious faith over the last decade declined from 54% in 2014 (when the Center last asked this question) to 47% today.

Still, with religiously unaffiliated Americans rising steadily as a share of the U.S. population, the share of people who say religion is losing influence in American life continues to far exceed the share who say religion’s influence is growing (by a 74% to 23% margin). And those who say it has gotten harder to be a deeply religious person in the U.S. continue to outnumber those who say it has become easier (by a 47% to 13% margin).

And over the past year, there is no sign that any religious group analyzed in the survey has increasingly come to view their side as “winning” on the political issues that matter most to them. Indeed, majorities in every religious group analyzed in the study – ranging from 62% of Black Protestants to 78% of White evangelical Protestants – say their side has been losing more often than winning on the political issues that matter to them.

This also includes people who are religiously unaffiliated (those who describe themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”). Three-quarters (74%) of unaffiliated U.S. adults (sometimes called “nones”) say their side has been losing. (For additional discussion of the public’s view of whether their side has been winning or losing in politics, see “Growing share of Americans say their side in politics has been losing more often than winning.”)

Views about how major parties, Biden administration approach religion

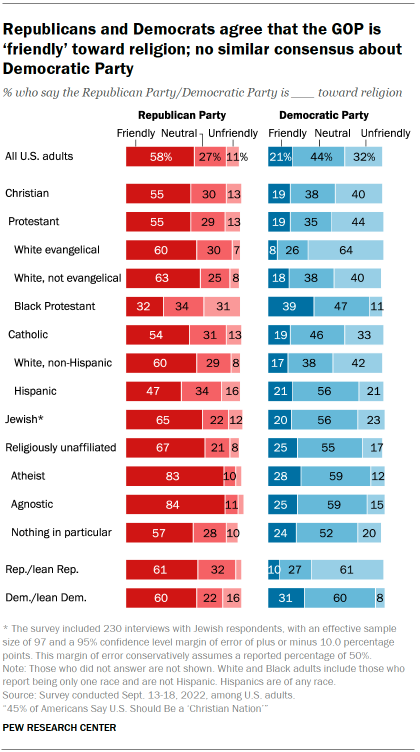

In addition to asking about the Supreme Court’s stance toward religion, the survey also asked similar questions about the country’s two major political parties and the Biden administration. Republicans and Democrats mostly agree that the Republican Party is “friendly” toward religion; 61% of Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party say this, as do 60% of Democrats and Democratic leaners.

Partisans differ sharply, however, in their perceptions of the Democratic Party. Six-in-ten Democrats say their party is “neutral” toward religion, and roughly three-in-ten say their party is friendly toward religion. Just 8% of Democrats view the Democratic Party as “unfriendly” toward religion. In sharp contrast, most Republicans (61%) say the Democratic Party is unfriendly toward religion, while 27% say it is neutral and just 10% say it is friendly.

Majorities in most religious groups say the Republican Party is friendly toward religion, although Black Protestants (32% of whom view the GOP as friendly to religion) and Hispanic Catholics (47%) are two exceptions. White evangelicals, meanwhile, are the only religious group in which a majority views the Democratic Party as unfriendly to religion (64%).

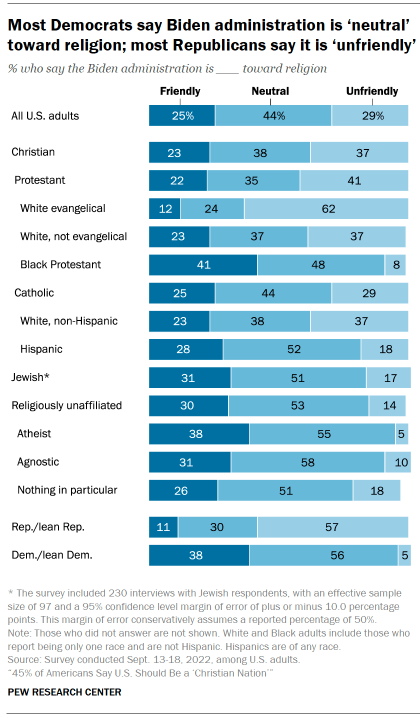

Opinions about the Biden administration’s approach to religion resemble views toward the Democratic Party. Most Democrats say the Biden administration is neutral toward religion, while a sizable minority say it is friendly and just 5% say it is unfriendly. By contrast, most Republicans (57%) say the White House is unfriendly toward religion, while three-in-ten say it is neutral and just one-in-ten say it is friendly.

A plurality of all U.S. Catholics (44%) say the Biden administration is neutral toward religion, while 29% say it is unfriendly and 25% say it is friendly to religion. (Biden is the nation’s second Catholic president.)

Partisanship, religion and views of U.S. as ‘Christian nation’

The survey finds that White evangelical Protestants are more likely than other Christians to say the founders intended for America to be a “Christian nation,” that the U.S. should be a Christian nation today, and that the Bible should have more influence over U.S. laws than the will of the people if the two conflict.

But these sentiments also are commonplace among other Christian groups – and by no means exclusive to White evangelicals. For example, half of Black Protestants say the Bible should have more influence on U.S. laws than the will of the people if the two conflict. About half of White Protestants who are not evangelical say the U.S. should be a Christian nation. And roughly six-in-ten Catholics say they believe the founders originally intended for America to be a Christian nation.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the view that the U.S. should be a Christian nation is far less common among non-Christians than among Christians, as is the view that the founders originally intended for the U.S. to be a Christian nation (though 44% of non-Christians express the latter view). But non-Christians are more likely than Christians to say they currently see the U.S. as a Christian nation (40% vs. 30%).2

Three-quarters of Republicans (76%) say the founders intended for the U.S. to be a Christian nation, compared with roughly half of Democrats (47%). Republicans also are at least twice as likely as Democrats to say that America should be a Christian nation (67% vs. 29%) and that the Bible should have more influence over U.S. laws than the will of the people if they conflict (40% vs. 16%).

Americans of different ages also differ on these questions, with older Americans much more likely to express the desire for America to be a Christian nation. For example, 63% of Americans ages 65 and older say the United States should be a Christian nation, compared with 23% of those ages 18 to 29. Other studies consistently find that older Americans are far more likely than younger ones to identify as Christians.

Other key findings include:

- A third of U.S. Christians say “being patriotic” is “essential” to what being Christian means to them, while four-in-ten say it is “important, but not essential” and roughly a quarter (27%) say being patriotic is “not important” to what it means to be Christian.

- There are only modest differences among White evangelical Protestants, White Protestants who are not evangelical, and White Catholics on this question.

- Black Protestants and Hispanic Catholics are somewhat less inclined than their White counterparts to cite patriotism as an essential element of Christianity. Christians from all backgrounds are instead much more likely to rank believing in God, living a moral life and having a personal relationship with Jesus Christ as “essential” elements of Christianity.

- Roughly four-in-ten U.S. adults say churches and other religious organizations have too much influence in politics – on par with the share who said this in 2017, and slightly higher than the share who said it in 2019. Roughly one-third now say churches and religious organizations have about the right amount of sway in politics, while 22% say they do not have enough political influence.

- The survey suggests that more Americans see religion as a positive influence in American life than a negative one. Four-in-ten U.S. adults say religion’s influence is declining and that this is a bad thing. Approximately one-in-ten say religion’s influence is growing and that this is a good thing. Roughly half, then, express a positive view of religion in these questions. By contrast, about a quarter of U.S. adults express a negative view of religion by saying either that religion’s influence is waning and that is a good thing, or that religion’s influence is growing and that is a bad thing. (See Chapter 1 for additional details.)

Guide to this report

The remainder of this report describes these findings in additional detail. Chapter 1 focuses on the public’s perceptions of religion’s role in public life. Chapter 2 examines views of religion and the Supreme Court. And Chapter 3 focuses on views of the U.S. as a “Christian nation” and perceptions of “Christian nationalism.”